I joined a Council of Europe workgroup on Quality job creation through social links and social innovation (the social innovation part is a recent add to the group’s name, and I think I am partly responsible for the add). One of the issues we are discussing is this: given that there is an interesting group of people who started calling themselves social innovators; given that these people seem to have potential for improving the society they (and we) live in; given that they look like a new kind of social and economic agent, as such requiring a new kind of public policy – the ones in place for firms and nonprofit orgs might not work in their case; given all this, it follows that public authorities might soon be required to do new things, perhaps radically new ones. That’s great; but how do public authorities actually learn?

I joined a Council of Europe workgroup on Quality job creation through social links and social innovation (the social innovation part is a recent add to the group’s name, and I think I am partly responsible for the add). One of the issues we are discussing is this: given that there is an interesting group of people who started calling themselves social innovators; given that these people seem to have potential for improving the society they (and we) live in; given that they look like a new kind of social and economic agent, as such requiring a new kind of public policy – the ones in place for firms and nonprofit orgs might not work in their case; given all this, it follows that public authorities might soon be required to do new things, perhaps radically new ones. That’s great; but how do public authorities actually learn?

This looks like a relevant question to me. I have worked on pilot government initiatives hailed by some as innovative, like Kublai or Visioni Urbane; the challenge they now face is integration into mainstream policy, becoming a part of the default arsenal for their parent authorities to do their job. Thanks to the Council of Europe’s support I have been able to look deeper into the issue. My provisional conclusion is that the prevailing learning model for public authorities is rational-Weberian and way off the mark. Here’s how it works:

- a new issue, after its importance has been validated by the scientific community, gains importance in the eye of the public opinion.

- politicians, competing for votes, include it in the list of issues they promise to tackle once elected.

- after taking office, representatives embed action to be taken thereabout into law.

- new law is enacted into policy

This model is elegant but useless. It only works if (1) alternative courses of actions can be identified, discussed and selected already in the democratic debate phase; (2) the electorate has effective means to enforce their pact with its representatives, constraining them to keep their promise by making law; (3) law enactment is “linear”, i.e. a law translates unambiguously in a course of action at the level of the executive branch (the main tool for law enactment is generally assumed to be the impersonal, rational Weberian bureaucracy); (4) and policy is a one way street: government acts upon society, trying to mould it according to its goals, whereas society does not exert any influence on government, save through the democratic process. None of this is even remotely true.

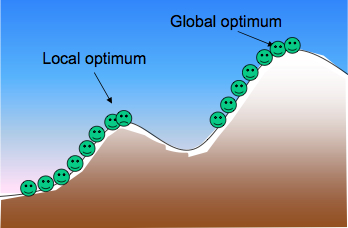

So what? So it makes more sense to abandon Weber and the mechanism metaphor for framing governance, and embrace an ecosystem metaphor instead. I propose to look at public authorities as complex adapive systems, coevolving with society and the economy. Teaching them to deal with social innovation – or anything they never experienced before – means helping them to think of economic and social agents as driven by evolutionary forces that reward the fittest. Policy, then, works best by shaping the fitness landscape, and letting agents work their way through it towards the desired outcome. It is a policy that enables and incentivizes agents to give input, rather than forcing outcomes top-down. This has clear implication for designing policies in practice. One of them is that a constitutional architecture that enables bottom-up learning (like Common law) is inherently superior to one that does not.

If you care about this topic, you can read the paper: the Council of Europe authorized me to share it online. Thanks to Gilda Farrell and Fabio Ragonese for the kind concession.

the problem is not (only) policy.

the problem is politics.

see Frank Moulaert and Erik Swyngedouw