I care about public policies, and try to contribute to their betterment. The road I am exploring is to take advantage of the social Internet to connect citizens among themselves and with government institutions to assess governance problems, design solutions and implement them – all in a decentralized fashion. I wrote a book to show it has been done, and to argue for it to be done more.

But it remains a tough sell. Many decision makers remain skeptical: why should online conversations converge onto evidence-based consensus? A few people who share a common work method can make an effective group, but a large number of very diverse and self-selected citizens – what I have been arguing for – is likely to collapse under the weight of trolling, controversy and sheer information overload. We have examples in which this did not happen: but we don’t have a theory to guide us in designing conversation environment which produce the desired results. Not good enough.

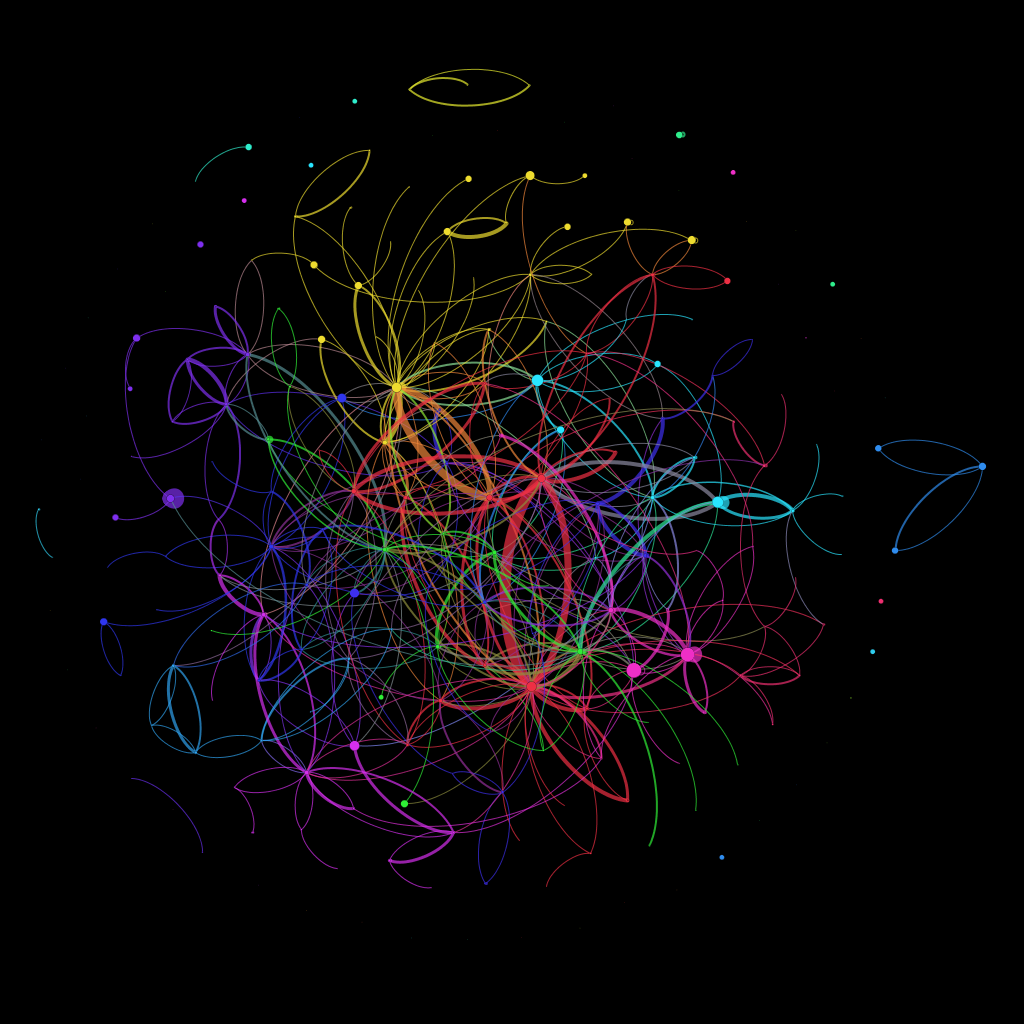

Some work I have been doing recently might provide a lead. As the director of Edgeryders, I marveled at the uncanny ability of that community to process complex problems – as I had done many times before in my years as a participant to online conversations. But this time I had access to the database, and – together with my colleagues at the Council of Europe and the Dragon Trainer project – I used it to reconstruct a full model of the Edgeryders conversation as a network. The network works like this:

- users are modeled as nodes in the network

- comments are modeled as edges in the network

- an edge from Alice to Bob is created every time Alice comments a post or a comment by Bob

- edges are weighted: if Alice writes 3 comments to Bob’s content an edge of weight 3 is created connecting Alice to Bob

I looked at the growth over time of the Edgeryders network as defined above, by taking nine snapshots at 30 days intervals, working backwards from July 17th 2012. For each snapshot I looked at four parameters:

- number of connected components (“islands” in the network)

- Louvain modularity of the network. This parameter identifies the network’s subcommunities and computes the difference between its subcommunities structure and what you would expect in a random network. Modularity can take any value between 0 and 1: higher values indicate a topology that is unlikely to emerge by chance, so they are the signature that some force is giving the network its actual shape; low values mean that the breakdown into subcommunities is weak, and could well have emerged by chance.

- for modularity values indicating significance (above 0.4), the number of subcommunities in which the network is broken down by the Louvain algorithm

These indicators for Edgeryders agree that there is no partitioning in the network. All active members are connected in one giant component, whose modularity values stay consistently low (around 0.3-0.2) throughout the period analyzed. This is not surprising: my team at Edgeryders had clear instructions to engage all newcomers into the conversation, commenting their work (and therefore connecting them to the giant component). From a network perspective, the job of the team was exactly to connect every user to the rest of the community, and this means compressing modularity.

Next, I looked at the induced conversation, the network of comments that were not by nor directed towards members of the Edgeryders team. It includes conversations that the Council of Europe got “for free”, without involving paid staff – and in a sense the most diverse, and therefore the most interesting. To do this, I dropped from the network the nodes representing myself and the other team members and recomputed the four parameters above. Results:

- there is a significant number of “active singletons”, active nodes that are only talking to the team members, but not to each other. This might indicate a user life cycle effect: when a new user becomes active, she is first engaged by a member of the paid team, who tries to facilitate her connection to the rest of the community (by making introductions etc. My team has specific instructions to do this). The percentage of active singletons decreases over time, from about 10% to less than 5%.

- not counting active singletons, there are several components in the induced conversation network. A giant component emerges in February; from that moment on, the number of components is roughly constant.

- the modularity of the induced conversation network (excluding singletons) is high throughout the observation period (over 0.5),

- the modularity of the giant component is also high throughout the period (over 0.5). Interestingly, modularity grows in the November-April period, indicating self-organization of the giant component. In February it crosses the 0.4 significance threshold

- the number of subcommunities in which the Louvain algorithm partitions the giant component also grows over time, from 3 in April to 11 in July

Subcommunities are color coded. Knowing Edgeryders and being part of its community (and having access to non-anonymized data), I can easily see that some of those subcommunities correspond to subjects of conversation. For example, the yellow group in the upper part of the graph is involved in a web of conversation about the Occupy movement and how to build and share a pool of common resources. Also, looking at the growth of the graph over time, subcommunities seem to grow sequentially more than simultaneaneously. This might be related to the management structure of Edgeryders: we launched campaigns (roughly one every four weeks) to explore broad issues that have to do with the transition of youth to adulthood. Examples of issues are employment/income generation and learning. So, an interpretation could be this: each campaign summoned users interested in the campaign’s issue. These users connected to each other in clusters of conversation, and some of them act as “bridges” across the different cluster, giving rise to a connected, yet highly modular structure. The video above has some nice visualizations of the network’s growth and of the most relevant metrics.

This looks very much like parallel computing (except this computer is made of humans), and could be the engine of scalability. As more people join, online conversation does not necessarily become unmanageable: it could self-organize into clusters of conversation, increasing its ability to process a certain issue from many angles at the same time. Also, this interpretation is consistent with the idea that such an outcome can be helped by appropriate community management techniques.

Ten years ago, Clay Shirky warned us that communities don’t scale. He was right, by his own definition of community – which is what in network terms is called a clique, a structure in which everybody is connected to everybody else. I would argue, however, his definition is not the most appropriate to online communities. Communities do scale, by self-organizing into structures of tight clusters only weakly connected to each other.

If we could generalize what happens in Egderyders, the implications for online policies would be significant. It would mean we can attack almost any problem by throwing an online community at it; and that we can effectively tune how smart our governance is by recruiting more citizens. appropriately connected, into it. We at the Dragon Trainer project are following this line of investigation and developing tools for data-powered online community management. If you care about this issue too, you are welcome to join us onto the Dragon Trainer Google Group; if you want to play with Edgeryders data, you can find them on our Github repository.

Coming soon: posts about conversation diversity and community sustainability based on the same data.

The analysis is fascinating but i still find the relevance for policy-making quite weak. Policy by definition pursues the public interest. I am personally convinced that structuring appropriatly the consultation with informed citizens can improve the public-orientation of policy, and in other ways improve its quality. However, showing that communities scale up and in doing so they partition into sub groups of discussion does not seem to bring home the point that conversations improve policy definition. This can be proven in specific cases (only?) by showing that the quality of policy deisgn has improved through expanded consultation of this kind: evidence of this is scant not only in your work, but in general.

Well, suppose you are running an online consultation. Unless the consultation is very uninteresting, like “hey, citizens, do you like what we are doing?” (requesting basically a one-bit, yes/no information), or “choose one of four alternatives” (which is a poll, resulting in “26% of citizens prefer alternative A”), you might be interested in using it as a discovery tool. I seem to recall you signing an article called “harnessing the unexpected”. 😉

If you believe my conjecture, you could indeed use it to discover information (and perhaps even solutions) you had not thought of before. How? By attracting diverse people; giving them a relatively unbridled interaction space (multiple choice questionnaires perform obviously very badly in this respect); and deploying some animation.

Then, even if the exercise works very well and you get a lot of fresh information out of it, you might still design bad policy. There are a lot of factors involved in policy making beyond good ideas (political acceptability and administrative constraints come to mind); also, while I am convinced that online communities are very good at exploring issues and processing large masses of information, I am not so convicned they are good at making decisions too.

Alberto: Thank you for reflection.

This is a problem that concerns me very much, as you said: how can we make the experience of Wikipedia to create “WikiGovernments” or rather “WikiSocieties”? (Following your terminology, I should use the Wikicrazia word 🙂

I think we are still far from being able to define a methodology for this question. I think in a methodology, with a minimum success rate, that it could help governments to gather collective intelligence.

Concepts like scalability haven’t yet been explored sufficiently, this post providing here is very interesting in order to tackle this problem from a new perspective.

Please notify me if you progress more in this area.

hello alberto

from my point of view of coordinator of the Digital agenda of Bologna Municipality I have observed phenomena which can confirm your analysis.

For the first time, we have tried to map the digital activities and through projects such as incrediBOL for startups, Di nuovo in centro and TDays for a new urban mobility, PAES for activities to reduce environmental impact, Bologna estate to support summer cultural activities, for example, we have identified some communities using instruments calibrated depending on the available energy (human resources principally) like blogs, web pages and social media, using online form and questionnaires.

So I can confirm that there are vertical comunities with different tags and interests like meeting point. We are now considering to try this approach on the “intercultural” activities” with another (new?) community in the process.

The data I have is about access to events or to the web sites, about fans / followers on social media and about questionarios completed so I do not provide complete graphic like yours but the feeling is that now the next step would be to provide a support to all projects, not only strategic consulting but also horizontal community management, to create a large community made up of city users + lovers of the city of Bologna. It ‘s a matter of resources but also because the projects that I have listed are in different departments with different logic and grammar. If every project were indicated by different colors we could map the relationships between nodes, highlighting ties between different communities and to the core, I think your analysis is confirmed with a change that still does not change your initial thesis, indeed: A Bologna does not have 2 levels (your staff and between communities) but 3 levels ( communication staff that speaks to the various departments who in turn manage the community).

In Matera we gonna speak about this!

Well, Michele: would you be interested in a partnership? My tiny team and I can probably finish some version of this project alone, but it gets better with every addition of people, approaches, sub-projects. If you launch a community, it would be quite simple to design for data extraction in a way that enables this kind of analysis: and then we could compare notes. This is important because requests for functionalities of DT are going to be made by data analysts who need certain data in order to make certain inferences. See this thread for an example.

Other ways in which you could collaborate are helping with development, helping assemble the community around the project etc. Yes, let’s definitely talk in Matera.

It would be great! a possible synergy between your group and the municipality of Bologna would lead to a new idea of civic network. Bologna could be the ideal laboratory after the civic network Iperbole, born in 95. For now considers that for now all the communities converse on different (and private) platforms…

Alberto,

Very interesting stuff, loved reading your post and had to re-read it twice (ok im lying, 3 times) in order to get some the points and extrapolate their implications for the work we do within UNDP in Montenegro (this isnt necessarily unique to Montenegro, but we see a lot of ‘public consultations’ taking place that merely serve the purpose of ticking the box- they’re state centric, tend to involve citizens at a relatively late stage with little or no scope for real influence, and lacking user perspective).

This fall we’re about to launch a public consultation process on establishment of several regiona parks in the country, aimed at rural parts of the country with low levels of quality infrastructure… and we’re thinking of ways in making that process meaningful and engaging. Your idea of ‘throwing online communities’ at an issue- it sparked an idea of actually involving a Diaspora, that returns to these places where Regional Parks will be formed from various corners of the world, in the process of consultations and getting their input on various management policies that the Government will be designing.

All in all, thanks for the post…looking forward to following your work closely on this!

Best

Millie

Hello Millie, you think it is not clear? I am trying my best not to be too technical.

My two cents: involving diasporas is definitely a good idea. The main reason is that they add diversity to the conversation and connect it to the wider world. To be fair, in my experience, involving anyone is mostly a good idea: there is no way to know in advance who is going to make the pivotal contributions, and the marginal cost of accommodating one more person in an online conversation is near-zero. In fact, to be honest, I don’t think the concept of “stakeholder” makes a whole lot of ex ante sense.

I wrote extensively about these things in a book called Wikicrazia, but it is in Italian 😉