“We have no idea how a press conference on Twitter is going to pan out, of course. But it sounds like fun, so we’ll try it anyway.” In their typical just-trying-stuff-out style, about a month ago, a bunch of people over at Edgeryders invented, more or less accidentally, a format we now call Twitterstorm (how-to). The idea is to coordinate loosely in pushing out some kind of content or call to action using Twitter. The first Twitterstorm was aimed at raising awareness of the unMonastery and its call for residencies; it worked so well the community scheduled immediately another one, this time to promote the upcoming Living On The Edge conference, affectionately known as LOTE3.

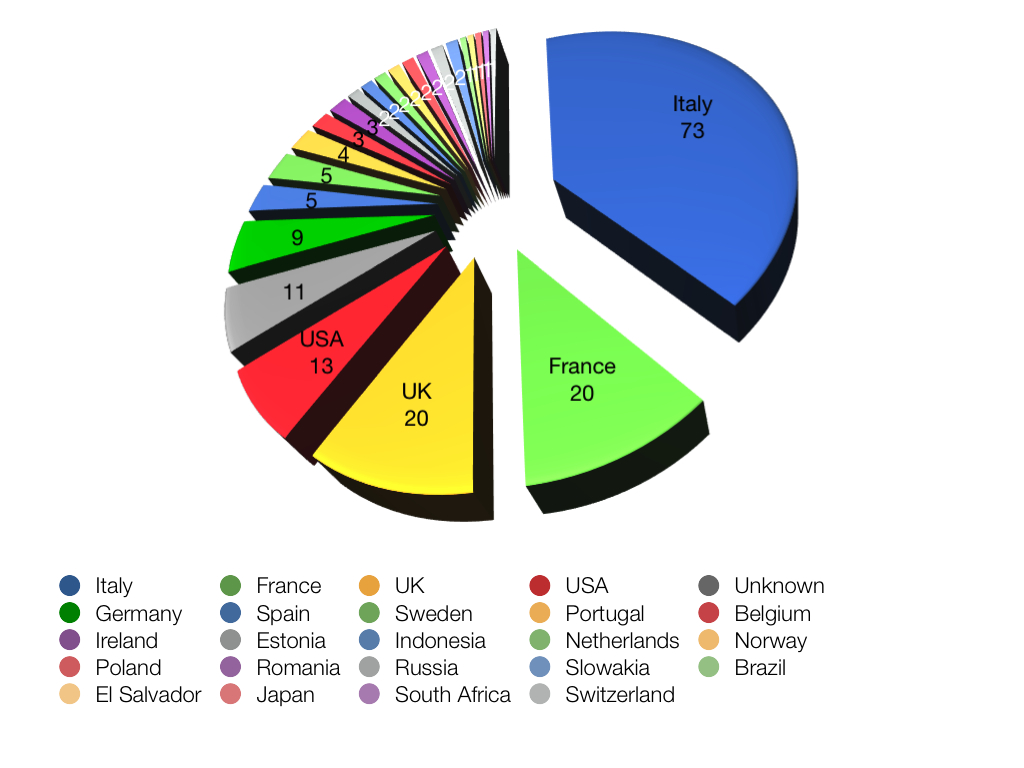

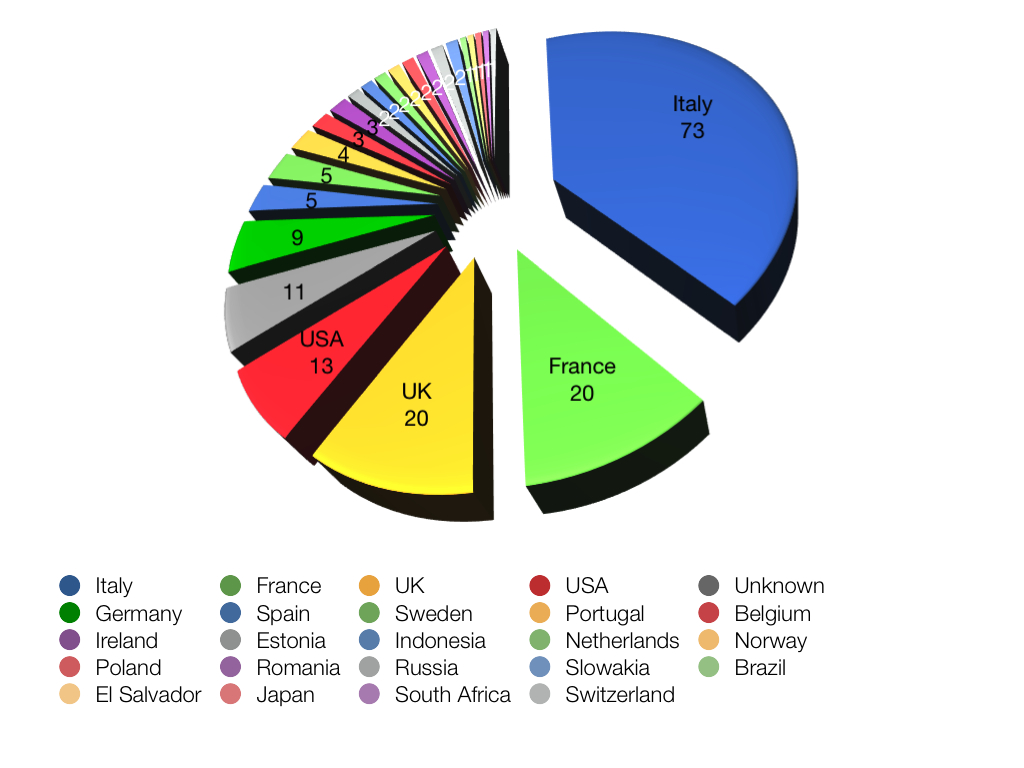

LOTE3 is to take place in Matera, Italy: the same city is to host the unMonastery prototype. So, we thought we would try to get people in Matera involved in the Twitterstorm, as an excuse to build some common ground with the “neighbors”. This second Twitterstorm took place on October 14th at 11.00 CET: like the first, it was a success, involving 187 Twitter users and 800 tweets (in English, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Swedish, French, German, Romanian) in the space of two hours. Apparently we reached 120,000 people worldwide, with almost 800,000 timeline deliveries (source). We hit number 1 trending topic in Italy (in the first Twitterstorm we hit number 1 in Italy and Belgium). Traffic to the conference website spiked. All of this was achieved by a truly global group of people: I have counted 23 nationalities. We promoted an event in Italy, but Italian accounts were less than 40% of those involved.

All this came at surprisingly little effort. People came out of the woodwork and participated, each with their own style, language and social media presence: despite all the diversity, the T-storm seemed to have some sort of coherence that made it simple to understand: people would notice the hashtag popping up in their timelines and go “Whoa, something’s going on here”. How is it possible that people with minimal coordination over the Internet; with such diverse backgrounds and communication styles; that don’t speak the same language and don’t even know each other, can cohere in an instant smart swarm and deliver a result? And, just as important: did we build community?

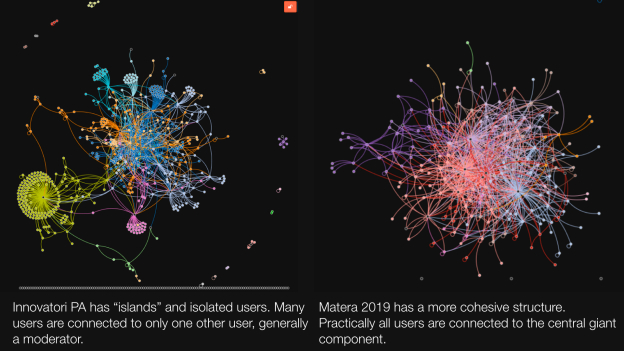

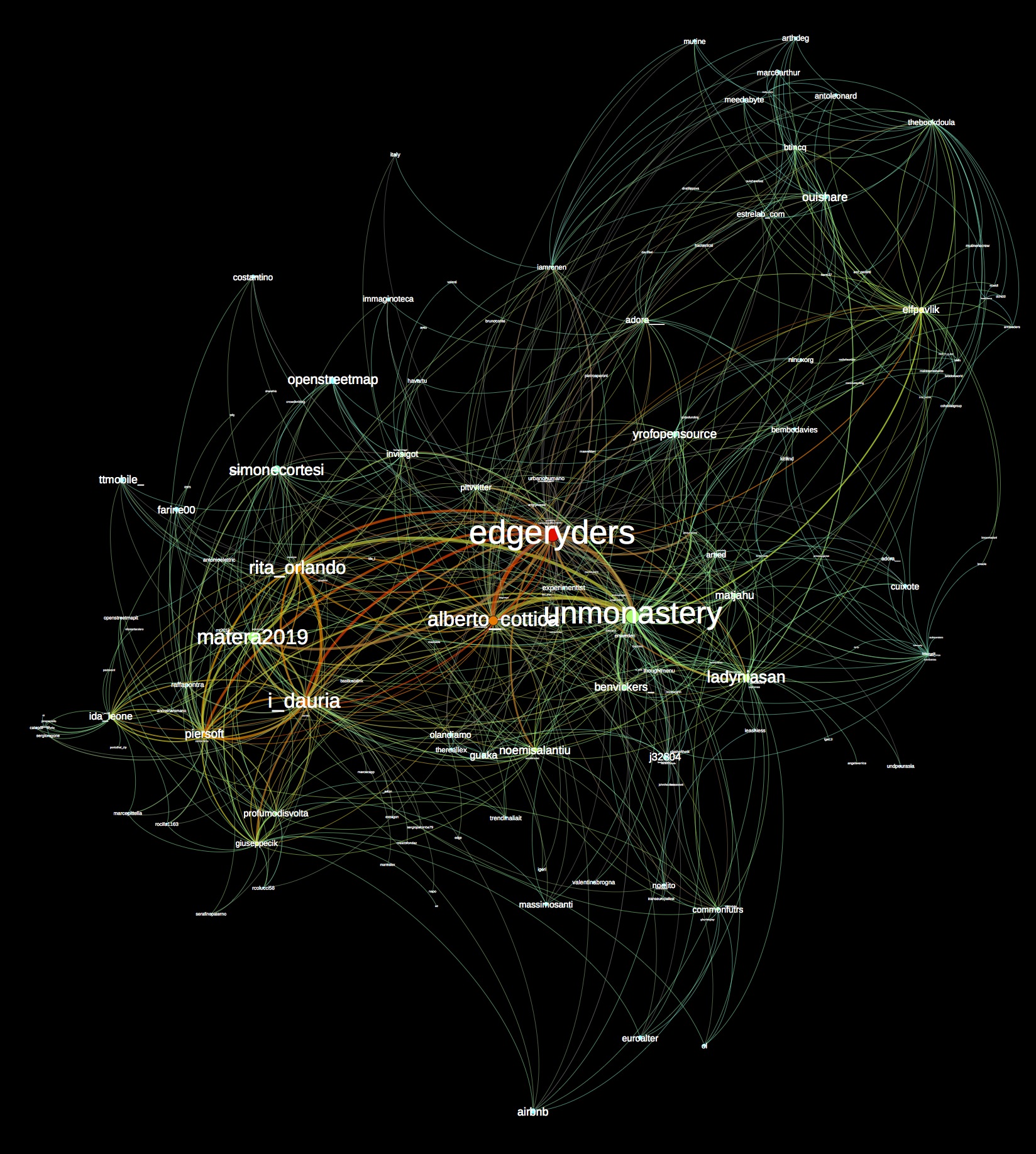

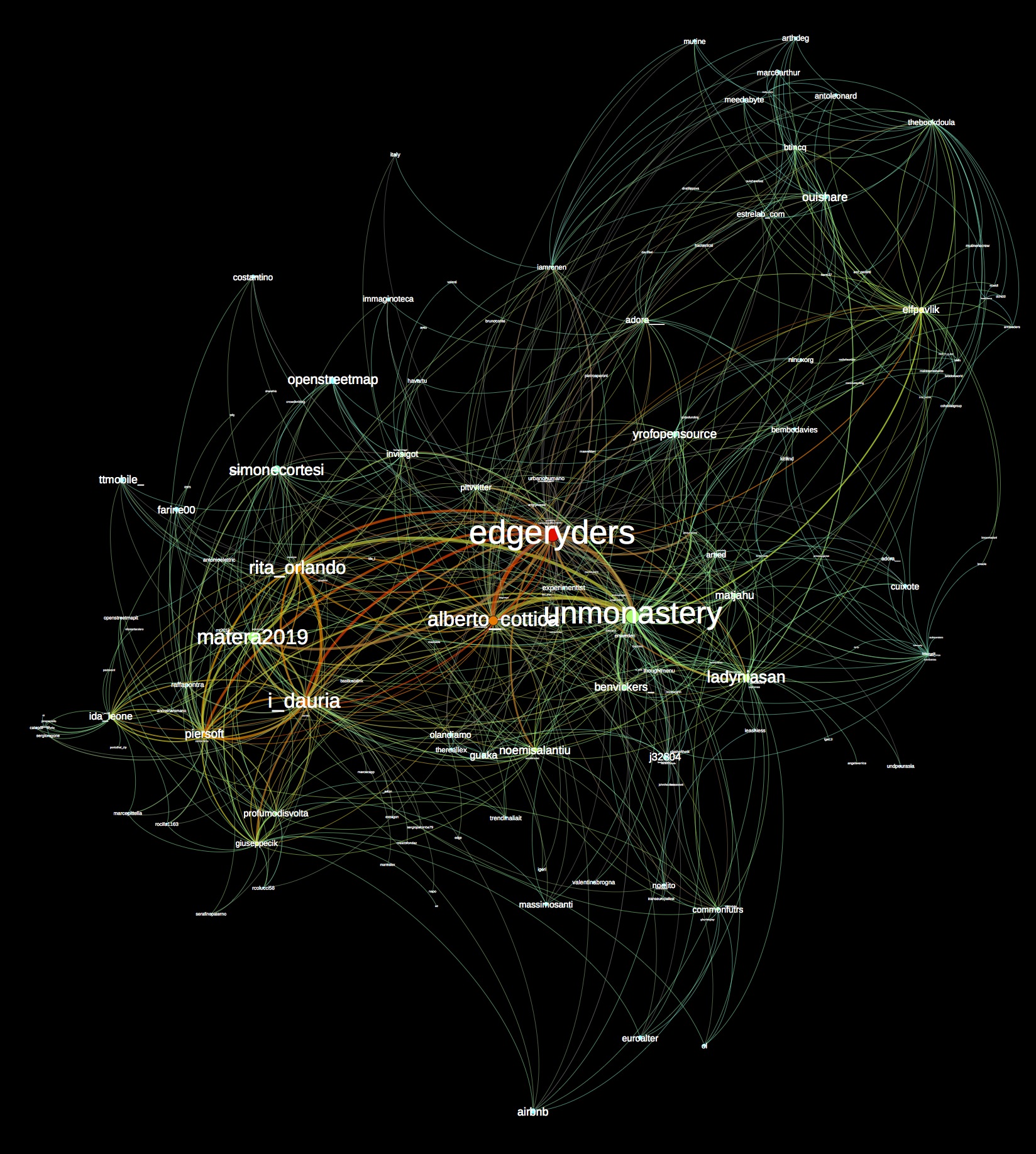

As I am fond of saying when complex questions are asked concerning online social interaction, turns out I can measure that. Let’s start with the first question, how can such coherence arise from so little coordination. The picture above (hi-res image) visualizes the Twitterstorm as a network, where nodes are Twitter accounts and edges represent relationships between them. Relationships can be of three kinds, and all are represented by edges. An edge from Alice to Bob is added to the network if:

- Alice follows Bob;

- Alice retweets one of Bob’s tweet that includes the hashtag #LOTE3;

- Alice mentions Bob with a tweet that includes the hashtag #LOTE3.

- Tweets that are neither replies nor retweets containing the hashtag are represented in the network as loops (edges going from Alice back to Alice herself).

- multiple relations map on weighted edges and are represented by thicker edge lines.

In the visualization, the size of the fonts represents a node’s betweenness centrality; the size of the dot its eigenvector centrality; the color-coding represents subcommunities in the modularity-maximizing partition computed with the Louvain algorithm (this network is highly modular, with Q = ~ 0.3). The picture tells a simple, strong story: the Twitterstorm group consists of three subcommunities. The green people on the left are almost all Italians, living in or near Matera, or with a strong relationship to the city. The blue people on the right are mostly active members of Ouishare, a community based in Paris. The red people in the middle are the Edgeryders/unMonastery community (note: the algorithm is not deterministic. In some runs the red subcommunity breaks down into two, much like in the network of follow relationships described below). Coordination across different subcommunities is achieved by information relaying and relationship brokerage at two levels:

- at the individual level, some “bridging” people connect subcommunities to each other. For example, alberto_cottica, noemisalantiu, i_dauria and rita_orlando all play a role in connecting the Materans to the edgeryders crowd. On the other side, ladyniasan and elfpavlik are the main connectors between the latter and the Ouishare group.

- at the subcommunity level, the ER-uM subcommunity is clearly intermediating between the Materans and Ouisharers.

- Each subcommunity is held together by some locally central, active individuals. You can see them clearly: piersoft, matera2019 and ida_leone for the Materans; edgeryders and unmonastery for the ER-uM crowd (these have many edges connecting them to the Materans): ouishare and antoleonard for the Ouishare group.

So, this is why doing the Twitterstorm seemed so effortless: this architecture allows each participant to focus on her immediate circle of friends, with no need to keep track of what the whole group is going. Bridging-brokering structures ensure group-level coherence.

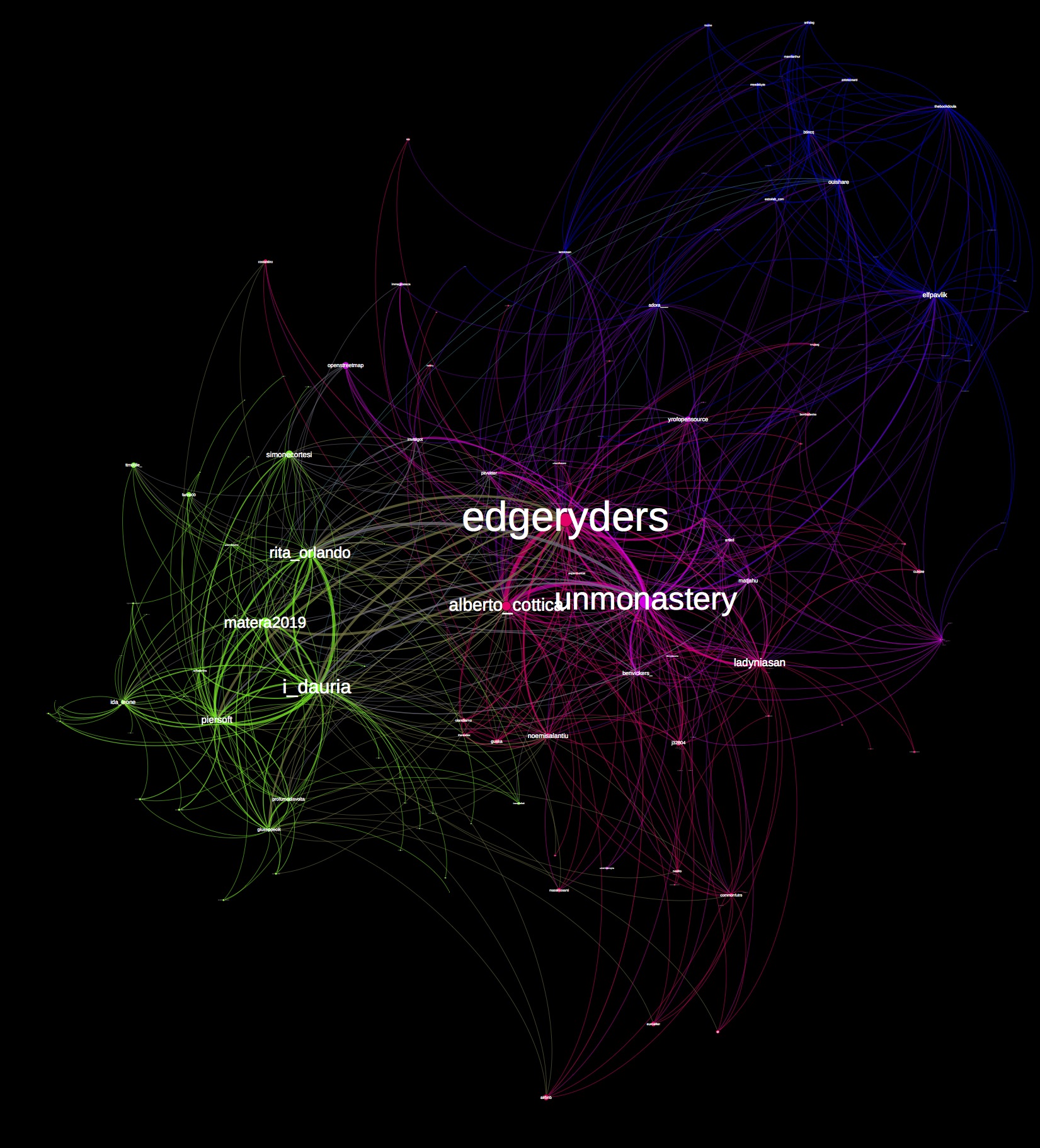

To answer the second question, “did we build community?”, I need to look into the data with some more granularity. We can distinguish edges between the ones that convey short-term static social relationships from those that represent active relationships. Following someone on Twitter is a static relationship: Alice follows Bob if she thinks Bob is an interesting person that shares good content. Typically, she will follow hime over a long time. Mentioning or retweeting someone, on the other hand, is an action that happens at a precise point in time. Based on this reasoning, I can resolve the overall Twitterstorm network in a “static” network of follower relationships – representing more or less endorsement and trust – and an “instant” network of mentions and retweets – representing more or less active collaboration in the Twitterstorm. The first of the two can be assumed to represent the pattern of trust that was built: it would be nice to confront it with the same network as it was before the Twitterstorm, but unfortunately our data do not allow us to do that. We can think of the second network as the act in which community was (or not) built.

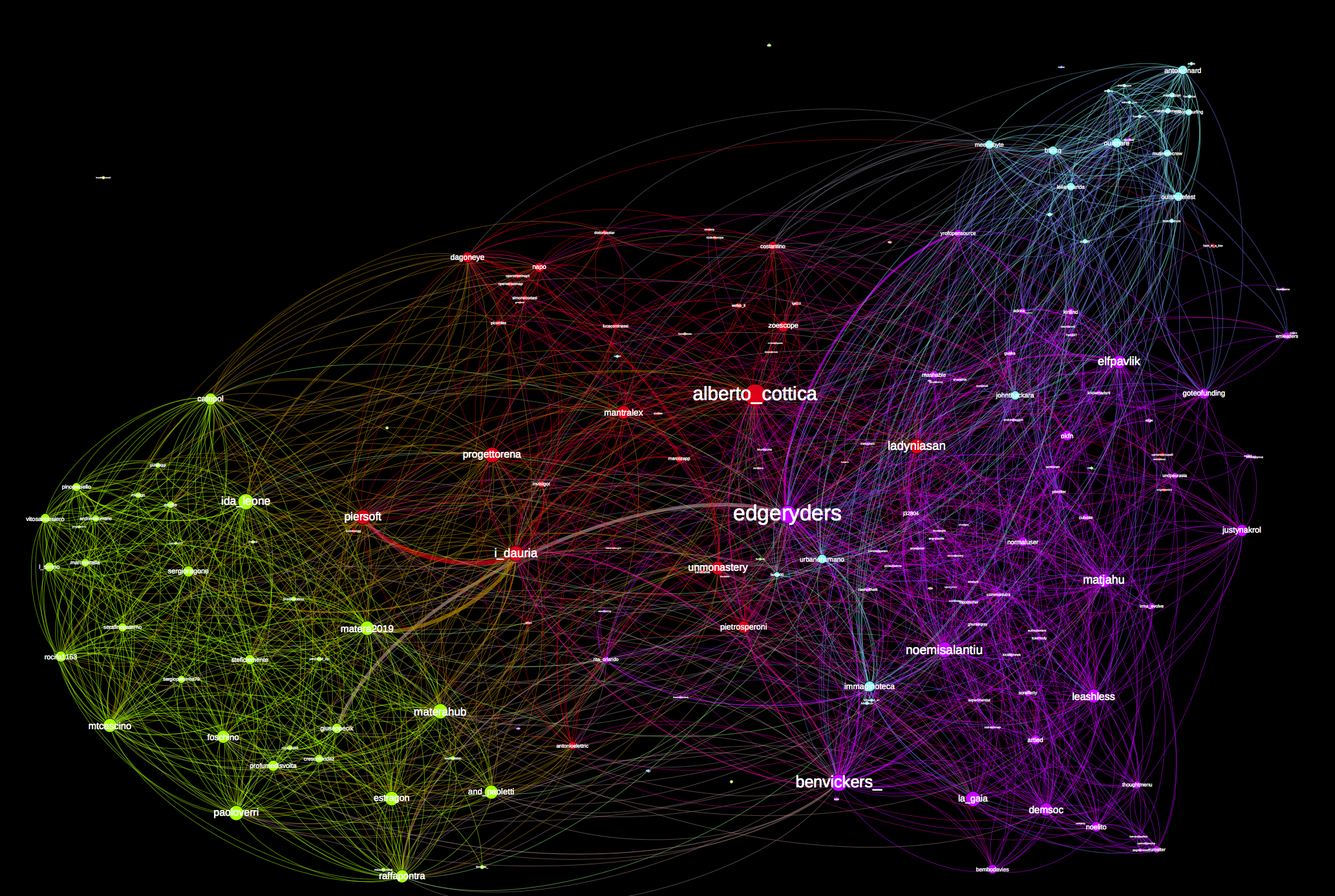

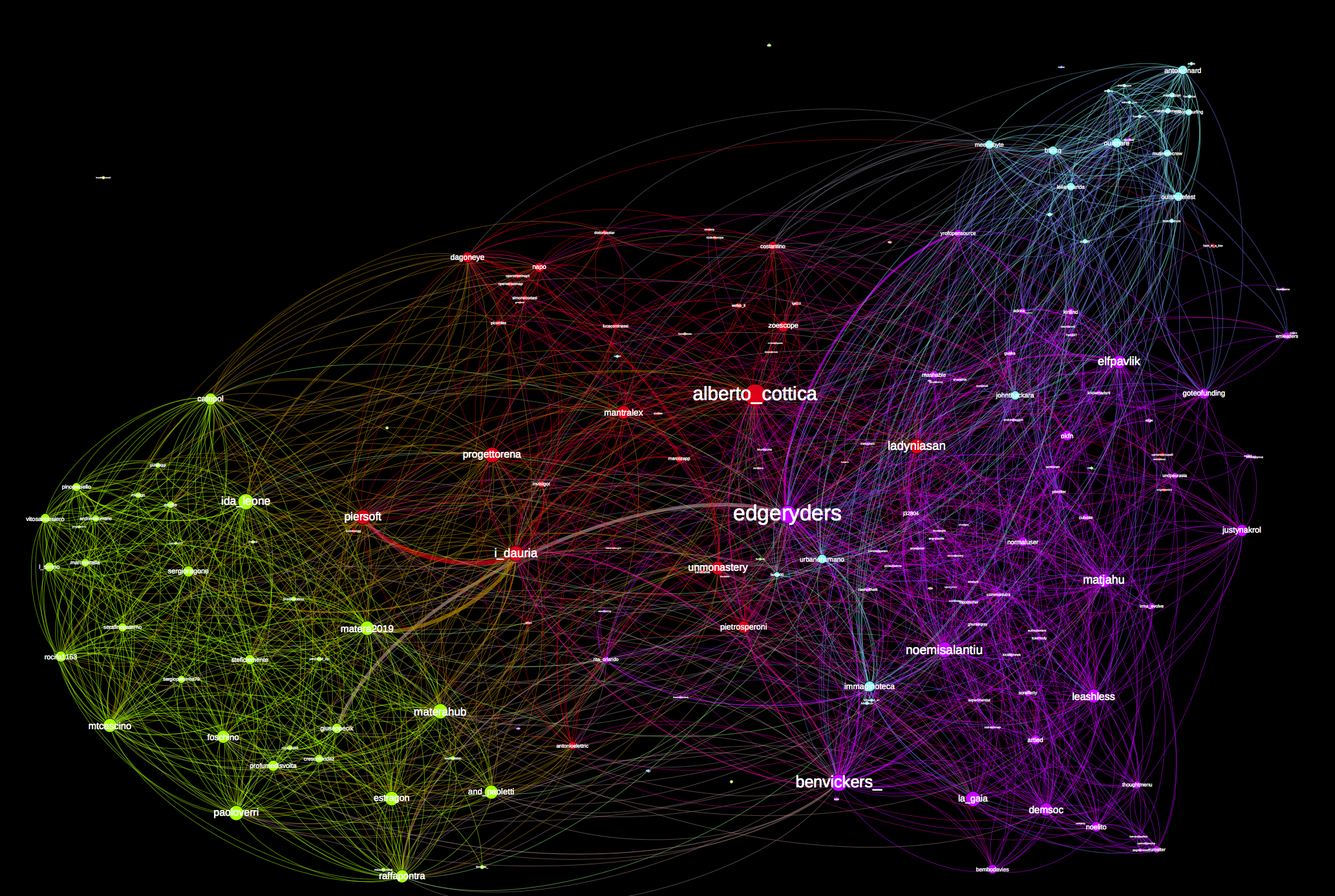

The network of trust is not so different from the overall one, but now there are four subcommunities instead of three (Q = ~ 0.33):

As before, the Matera group is clearly visible and depicted in green; the Ouishare group is also recognizable in blue. The red subcommunity now consists almost exclusively of Italians – most of them not in Matera, who have strong international ties. The ER-uM group is now depicted in purple. In terms of the static network, then, the coordination between Materans on one end and Ouisharers on the other end was intermediated twice: first by a (red) group of internationally connected Italians, then by a (purple) pan-European community gathered around Edgeryders. This is also another legitimate interpretation of the overall T-storm network.

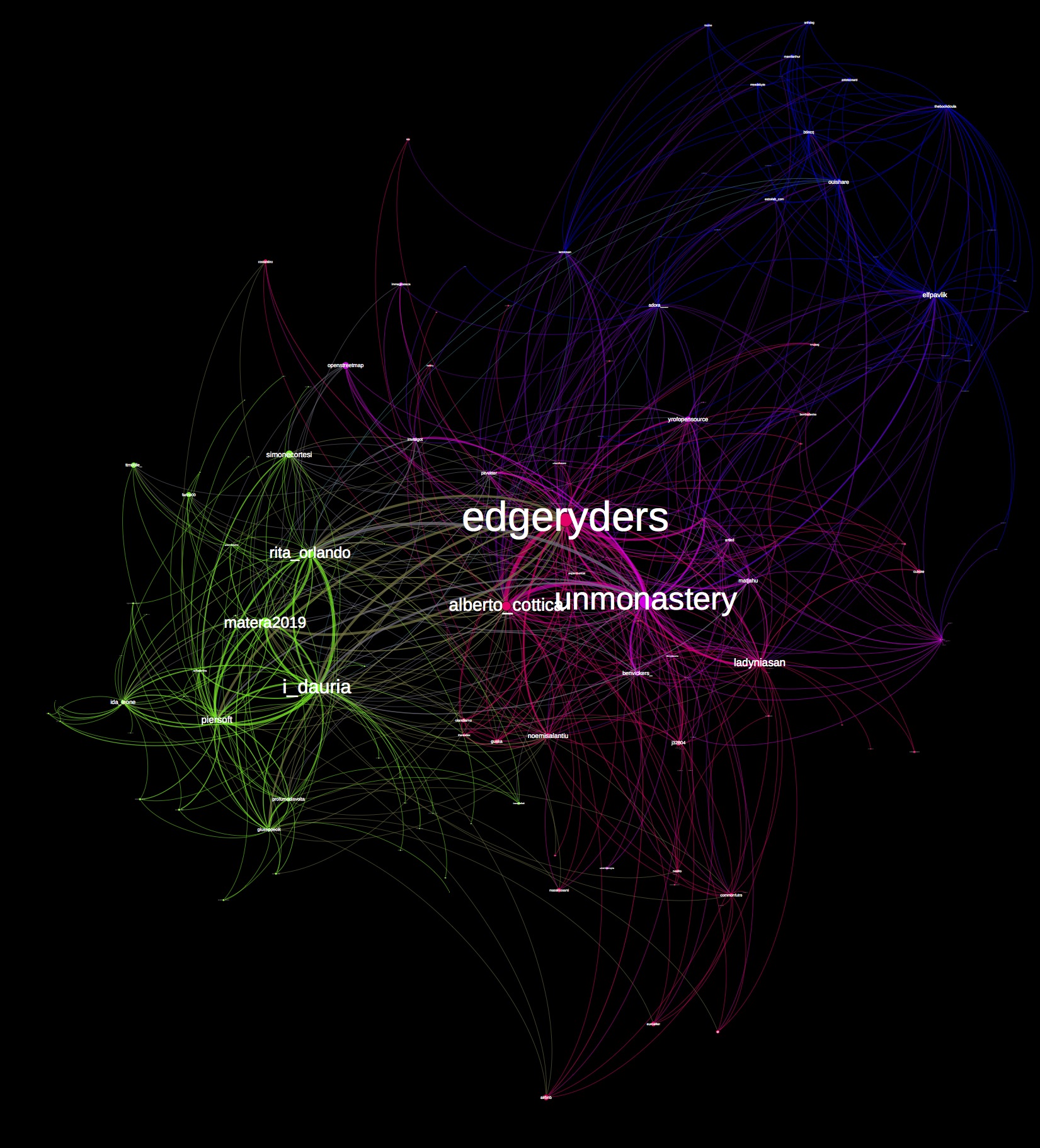

When we consider the “active” network of mentions and retweets that developed on Monday 14th, we find a rather different situation. Again, the components are four: but this time, the two central subcommunities seem more a mathematical effect of the high level of activity of the most active users, chiefly edgeryders, unmonastery and alberto_cottica, than clearly delimited subcommunities. Most of the modularity (which is even higher than in the two previous networks, Q = ~ 0.35) stems for the very clearly marked subcommunities to the left (Materans) and right (Ouisharers). No surprises here.

The picture below visualizes a higher weighted outdegree in redder colors on a blue-red spectrum. Redder nodes have been more active in mentioning and engaging the nodes they are connected to. The redder areas in the network are not within the subcommunities, but across them: most of the orange and red edges connect the Matera subcommunity (i_dauria, matera2019, rita_orlando, piersoft) with the ER-uM one (edgeryders, alberto_cottica). On the right, elfpavlik is busy building bridges between Ouisharers and ER-uM. So yes, we did build community. You are looking at community building in action!

Provisionally, as we wait for better data, we conclude that the Twitterstorm not only was dirt cheap, fun and good publicity, but it also left behind semi-permanent social effects, pulling the three communities involved closer together. Doesn’t get much better than that!