In November 2023, I was asked to keynote at something called the Space Economy Camp. The organizers were a diverse mix: the Complexity Economics Lab at Arizona State University; the 100 Years Starship Initiative, with its own literary prize; the Space Prize. The idea was this: 20 writers were selected via an open call, exposed to economics lectures, and put to work in small groups to imagine “sustainable, non-exploitative economies in space”.

I was one of the economists asked to give lectures. I decided to make it as practical as I could laying out some ideas from economics that, I thought, a sci-fi author might find useful in order to build fictional worlds with credible, if fictional, economies. Those ideas – useful or not, you be the judge of that – also applies to efforts of imagining economic systems outside of science fiction writing: for example to politics, or activism, or creating businesses or communities.

This post contains the editorialized notes from that lecture, reposted from Edgeryders.

1. Introduction and lecture outline

Worldbuilding is hard, as authors well know. In this lecture, we are going to take a look at the part of worldbuilding where you give your planet, eldritch dimension, fantasyland or post-climate change polity a believable, though obviously fictional, economy. In the time-honoured tradition, I have good news and bad news. The good news is that we have considerable latitude in designing your fictional economy, just as in inventing rituals, dress codes, weapons, and other technologies. The bad news is that coming up with a good design is nontrivial. But this is also good news, since overcoming difficulties with a creative act is what authors do, and it is perhaps the most fun humans can have.

In the lecture, We are going to reflect on some basic choices that we need to make when designing an economy. To help reflection, we invoke concepts from social sciences and economics.

| Concept in real life | Related concept in economics |

|---|---|

| Designing credible economies | Incentive compatibility |

| “Human nature” | Value theories |

| Institutions | Economic anthropology |

| Plausible histories | Subgame-perfect equilibria |

2. Suspension of disbelief

I am no author, just a lowly reader. But, when I read, I take pleasure from diving into an immersive, textured world that I can explore. This pleasure is enhanced by suspension of disbelief, the psychological state of someone who, willingly, suspends certain functions of critical thinking in order to enjoy the narrative. Emphasis is on “certain”. If I read The Lord of The Rings, I can allow myself to get worried about Sauron’s armies eating what’s left of the free peoples of Middle-Earth (though there is no Middle-Earth: if I look out the window, Brussels is right there). But some parts of my critical thinking are harder to switch off. If, in order to prevail in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, Gandalf had called in a drone strike on Mordor’s siege machines, that would have broken the suspension of disbelief, at least for me, and made my reading much less pleasant.

So, worldbuilding is a balancing act: the more space the author claims for imagining things that do not exist, the higher the potential entertainment value from the exoticism and mystery. But that space needs to be highly organised to avoid inconsistencies that puncture the bubble of the reader’s suspension of disbelief.

Careless depictions of the economy of fictional words can also rupture suspension of disbelief. A favourite example of mine is the use of coins cast in precious metal as currency in J.K. Rowling Harry Potter’s saga. The book makes it clear that the coins are precious and fungible (i.e. there is an incentive to steal them). They are kept in high-security vaults, guarded by goblins with great magical powers. This, however, does not quite gel: one imagines that, if the coins were really precious, wizards would simply magick them into existence. This would quickly lead to hyperinflation (depending on the magical cost of making new coins), which would drive the real value of those coins to near zero. I cannot justify those goblins.

Of course, this is a fantasy world, and you could always salvage it by inventing exceptions: for example, the wizards can magick up all sort of stuff, but not gold coins. Additionally, that no tracer spell can be put on coins so that they “know their master”, which would make them more like balances in a bank account, valuable but impossible to simply steal. But you see how this looks a bit contrived and “just so”.

Granted, readers can sometimes ignore the nagging feeling that something is off, and concentrate on the characters and the drama instead. This is easier in some subgenres than in others: readers of high fantasy novels are unlikely to pay close attention to economics, and indeed the Harry Potter’s saga is a huge success. So is Tolkien’s, and he got away with a complete disregard for anything to do with economics: who’s feeding, clothing and arming all these standing armies? Where are the breeders and stables to produce all those horses in Rohan, and would they not create some environmental damage? How is it that in besieged Minas Tirith there is no trace of a black market, like our grandparents experienced during World War 2 in most of Europe? On the other hand, if you are writing solarpunk sci-fi or cli-fi, alternative modes of organizing society are likely to be at the center of attention.

3. Incentive compatible mechanisms as a template for credibility

I propose that a good compass for figuring out whether a fictional economy is believable or not is its incentive compatibility. It goes through the concept of mechanism, associated with the names of Eric Maskin, Leonid Hurwicz and Roger Myerson. The basics are as follows:

- A mechanism is a manufactured environment for agents (normally people) to interact with one another (auctions, tax systems, social media…). Within the mechanisms, agents act according to their own objectives. [Maskin 2008]

- Designing a mechanism is about making its rules so that people in it spontaneously take the system in the direction that the mechanism designer wants to go.

- A mechanism is incentive compatible when every agent’s best strategy is to follow the rules, no matter what the other agents do [Hurwicz 1960].

In his Nobel lecture, Maskin asks three questions about mechanism design:

- When is it possible to design incentive-compatible mechanisms for attaining social goals?

- What form might these mechanisms take when they exist? Auctions, tax systems, elections, ritual combat, social media?

- When is finding such mechanisms ruled out theoretically?

They apply fairly directly to worldbuilding for science fiction authors! We can use them as a guide to imagine an economic system, for example that of a space economy. The authors can choose the system’s goals, then take on the mantle of the mechanism designer, and ask herself what form might incentive-compatible mechanisms take for those goals.

4. Incentives to do what? Introducing value theories

Incentive compatibility is about mechanisms being compatible with people’s incentives. Ok, but what are these incentives? What is it that people (be they humans, aliens, elves or robots) want? What do we value?

This is a philosophical question, and let us never forget that economics grew out of moral philosophy. Adam Smith was a professor of moral philosophy, and he authored a Theory of Moral Sentiments before The Wealth of Nations. The branch of economics dealing with it is called value theory. The most important thing to know about value theory is that it is inherently political and highly contested. Human communities in different times and places have adopted different value theories.

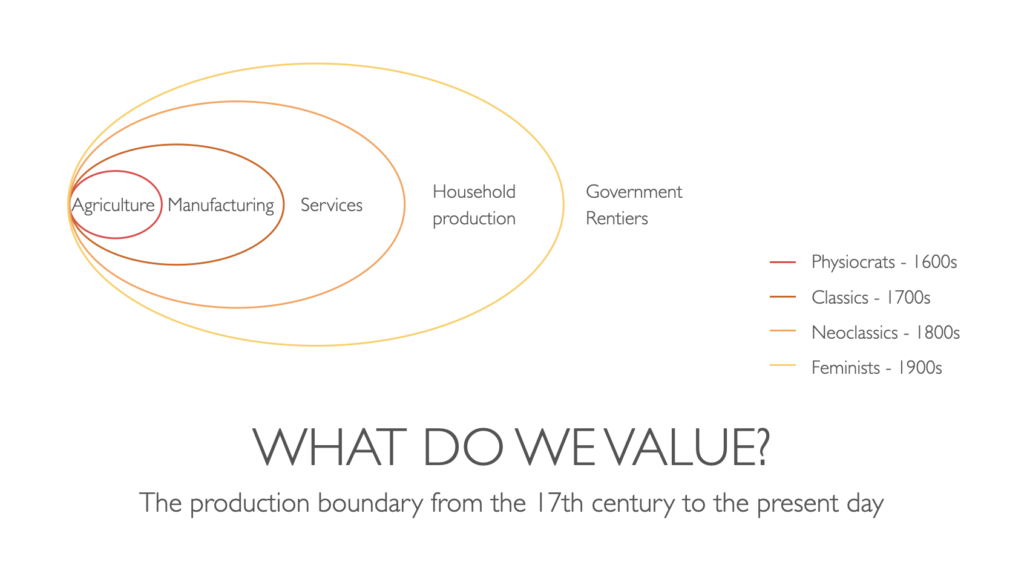

Consider, for example, the concept of production boundary, the imaginary line that divides activities that produce wealth to activities that merely redistribute it (I am borrowing this terminology from Mariana Mazzucato’s The Value of Everything). For example, imagine that Alice, a farmer, leases Bob’s land to grow wheat. Most economists would agree that Alice, when farming, produces wealth, whereas Bob, when collecting rent for the land, is simply redistributing to himself some of the wealth Alice has created. Another way to say this: Alice’s work (farmer) stands within the production boundary; Bob’s (landlord) stands outside it.

Mazzucato’s point is that the production boundary has shifted over the centuries, amidst much debate and political battles. A common pattern has been that, when a class of people managed to attain some power, it fought to get legitimized as productive, declaring whatever it was doing as “production”. If what counts as value depends on who you ask, it follows that value is not some kind of universal measurable property, like mass. It’s a convention, that results from a political process.

An interesting question around value theories is this: who is supposed to be doing the valuing? The physiocrats and the classical economists disagreed about where the production boundary lay, but they agreed that value was an objective characteristic of things. Both schools believed that Alice the farmer creates value, while Bob the landlord does not. Furthermore, they believed this was just a fact, that depended on no one’s personal opinions and views. The objective nature of value implies that societies can and do make collective choices that they believe to lead to producing more value. If the value of care work (feminist economics) or nature (ecological economics) are objective, then surely we must reward their production, just as we reward the production of food and manufactured goods (you could state that value is, instead of objective, intersubjective and historically determined, and the argument would still hold).

Marginalist economics has a different idea. Starting in the second half of the 1800s, this current of economic thinking maintains that value is subjective. If anyone is willing to pay for something, that something has value for that person. Marginalism posited that people wanted something called “utility”, and that different people would derive utility from different things. Its founders (Walras in France, Menger in Austria, Jevons and Marshall in the UK) had mathematical training and were keen to show that economics was “a real science” like physics. In order to make this idea of subjective preferences mathematically tractable, they assumed that, for each person, utility is an increasing function of her individual consumption of goods and services. Then, using calculus (invented in the 17th century), they could model individual choice as maximising an “utility function”, the arguments of which were individually consumed quantities of goods and services. Any collective dimension of value was discarded.

The founders of marginalism were well aware that theirs was a simplification, a thinking tool. Later, however, neoclassical economists started to think of this individualistic, subjective notion of value as true in itself. People, they thought, actually acted selfishly and in isolation: that was just human nature. Much sci-fi dystopia goes with the notion, and you can do so too. The main point of this lecture is that you don’t have to.

5. Underpinning the neoclassical theory of value: homo economicus

Neoclassical economists, then, posit that they have built a barebones model of human nature that (1) makes collective human behavior mathematically tractable and (2) despite its simplicity, captures the essence of how humans function. If both these claims hold, economists can build relatively simple models that will, nevertheless, capture the essence of human economic behavior and have explicative and predictive power. The idea of creating such a simplification for the purpose of doing economics goes all the way back to John Stuart Mill in 1836, and has later crystallized a model known as homo economicus. Looking at the conventional assumptions behind the economic theory taught in most university, homo economicus can be characterized precisely.

- He is motivated by self-interest alone.

- He has unlimited computational capacity (for example, computes the expected value of relevant stochastic variables).

- This model underpins Pareto-efficient general equilibrium theory, in which the individual pursuit of self-interest by each economic agent achieves socially optimal outcomes. This is the philosophical foundation of Ayn Rand’s “Virtue of selfishness”, or Gordon Gekko’s “Greed is good”.

The history of economic thinking has seen several critiques of the homo economicus idea. Among others:

- Most traditional societies are based on reciprocity (economic anthropology: Sahlins, Polany, Mauss…)

- Bounded rationality (Veblen, Keynes, Simon…)

- Inconsistent preferences for risk in investors (Tversky)

- Unstable, poorly defined preferences (behavioral economics: Kahneman, Thaler, Knetsch…)

- Not confirmed by experiments (experimental economics).

- Not confirmed by experience in actual societies (Sen).

In general, homo economicus is not a good simplification of “human nature” on which to hang a theory of value. It creates more problems than it solves.

6. Underpinning other theories of value: group selection and the evidence from ancient societies

A more plausible theory emerged in the 2000s from the work of a a school of biologists interested in cultural evolution, the interaction between evolutionary pressure, the human genome, and human cultures. The main idea is that, unlike other species, humans are subject to evolutionary pressure on two fronts: the individual level (from Darwin’s natural selection, common to all species), and the group level (from group selection) [Henrich 2016]. The fitness of a human individual depends both on the individual’s own fitness (for example his or her resistance to pathogens) and on the success of the group to which he or she is a member.

It turns out that successful groups are groups that are good at cooperation, which is intuitive and confirmed by plenty of ethnographic and archaeological evidence. So, evolution pulls humans in two opposite directions: it wants us to be more competitive, to obtain a better position within the group; but it also wants us to be more cooperative, to benefit from the success of the group with respect to other groups.

The main driver of the group’s success is the scale at which it can manage cooperation [Wilson 2012]. Given cognitive limitations, this means the successful human in a successful group must be able to cooperate with complete strangers (unlike, for example, chimps: troops of chimps that encounter a lone chimp from a different troop will typically kill the stranger on sight). This poses the additional problem of free riding: non-cooperators in a cooperative group will reduce the group’s performance, because they benefit from the “public goods” created by the group without contributing to them. For this reason, humans appear to have evolved methods to detect and expel the strangers in their midst. Experiments on infants as young as six months – and so untouched by education and value transmission – show that they react more favorably to others who speak their own dialect (even though they themselves have not yet learned to speak!). Biologists thinks that this “primary xenophobia” is innate, hardcoded into us at birth [Henrich 2016].

The late E. O. Wilson, perhaps the most accomplished scholar of cultural evolution, sums up his idea of “human nature” like this:

Individual selection is responsible for much of what we call sin, while group selection is responsible for the greater part of virtue. Together they have created the conflict between the poorer and the better angels of our nature.

So far the theory. Is it borne out by the data? An influential 2021 book by economic anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow claims it is. The Davids combine ethnographic and archaeological evidence to confute the mainstream narrative about the invention of agriculture. Such mainstream narrative is associated to scholars such as, among others, Francis Fukuyama, Steven Pinker and most recently Yuval Harari, and goes like this: for a long time, humans lived in small hunting-gathering bands. These early societies were free and equal. Women were not oppressed. But then, ten thousands years ago, agriculture was invented. Early farming societies had a decisive advantage, as they could hoard stocks in good years to weather the bad ones. But farming meant inventing and enforcing property rights, which meant top-down management and therefore hierarchies. Stratified classes appeared, themselves allowing cooperation on a larger scale and giving farmers further advantages over hunters-gatherers. Patriarchy also ensued.

According to the Davids, this story is largely a fantasy, originated (much like Hardin’s tragedy of the commons story) by deductive thinking from philosophical premises originated in the Enlightenment. We have evidence of socially stratified hunting-gathering societies; egalitarian farming ones; societies taking up, then abandoning farming; even societies that farmed in the summer, and hunted-gathered in the winter, changing their leadership structure and political order with the season. The Davids refer back to Marcel Mauss’s 1903 studies of Inuit societies, which indeed changed their societal arrangements in sync with the season (hierarchical and patriarchal in the summers, egalitarian and free-love practicing in the winters). Given the harshness of living conditions in the Arctic regions, Mauss expected that these variations could be explained by the material advantages they brought, but he had to conclude that they could not. In the words of the Davids:

“Yet even in sub-Arctic conditions, Mauss calculated, physical considerations – availability of game, building materials and the like – explained at best 40 per cent of the picture […] To a large extent, he concluded, Inuit lived the way they did because they felt that’s how humans ought to live.”

7. Implications for authors of economic science fiction

So, where does this leave us? In a fascinating place. Powered by group selection, all kinds of societal and economic arrangements seem to be possible. In fact, very many are certainly possible, and we know that because we have tried them before. Remember Maskin’s definition of mechanism, “a manufactured environment for agents to make decisions”? That definition also describes a society. A society is a mechanism, because it is manufactured – via a political process – by its members. This gives authors a license to use their imagination to design new and fascinating economies we, the readers, can try on for size. It also gives them a library of arrangements that have been (or are still being) tried, to take inspiration from.

To conclude this lecture, I want to briefly point to some historical and contemporary examples.

Monastic economies

In the 6th century, St. Benedict of Nursia codified in his Rule the “protocol” overseeing the interactions among monks in a monastery (6th century). He did not found an order, but the Rule went viral and was adopted by the nascent monastic movement. People who used it were more likely to run a successful monastery than people who did not; and so, by the time of Charlemagne all Europe was infrastructured with successful monasteries running on the Rule.

Benedictine monasteries were units of production, because, in order to be effective places of devotion, they needed to be autonomous from the secular world. Benedict was aware of this, and his Rule contains some economic prescriptions:

- Monks must price a little lower than seculars – doing otherwise would be avarice, a sin.

- Everything monks do must be high quality. It is work, and work is dedicated to God and leads to Him.

- Any profit you can make within these constraints is good, and you can use it to fund work that does not generate revenue.

This could not be more different from the neoclassical theory of labor supply, where a self-interested worker trades leisure for income; as well as from the theory of the profit-maximizing form. And yet, it worked extremely well. Monks made and ran inns; farmed the land; built water mills; created schools; copied and preserved manuscripts. At its peak, the famous Cluny Abbey served 10,000 warm meals a day to people in need. Also, this model is very stable, having been around (and prosperous) for 15 centuries straight. Even now, as a Benedictine superior told me, “we tend to to get prosperous, because monks work hard”.

Seasonal economies

These were described above in reference to the Inuit. The Davids again:

“In the summer […] property was possessively marked and patriarchs exercised coercive, sometimes even tyrannical power over their kin. But in the long winter months […] Inuit gathered together to build great meeting houses of wood, whale rib and stone; within these houses, virtues of equality, altruism and collective life prevailed.” [Graeber and Wengrow 2021]

Another traditional society with a similar arrangement are the Nambikwara in Northwest Brazil, studied by Lévi-Strauss in 1994.

Systems of cooperatives

Most economists, and most of the rest of us, think of the for-profit corporation as the “natural” form to organize economic activity. And yet, cooperatives are widespread all over the world. It is estimated that there are at least 280 million cooperators worldwide, and cooperatives have at least 27 million employees. Cooperatives lend themselves to self-organizing into “layers” to solve the problem of “make or buy”: a typical example is a group of farmers who grow grapes who join forces to commission a facility that will process the grapes of all of them into wine. This way, farmers can appropriate the added value of the transformation of their primary produce. One level above, you can find that the wine-making cooperatives of the same region can create a second-level coop to organize the distribution and marketing of the wine produced by all of them, and so on.

Europe has entire regions where most of the economy is cooperative. The most famous one is the Mondragon valley in Northern Spain, where an entire cooperative ecosystem of automotive manufacturing has come into being; several northern Italian regions are characterized by the prevalence of cooperatives in industries as diverse as agriculture, construction, insurance and banking.

Commons-based peer production

These are arrangements whereby non-hierarchical communities can maintain common resources (forests, fisheries, irrigation system) over time. They are very well documented: Elinor Ostrom won a Nobel for a 1990 book, Governing the Commons, where she not only looks in depth at case studies from Spain to Japan; she also comes up with 8 principles for designing the governance of a common resource. Principle 1 is “clearly define the group’s boundaries”, which goes back to Wilson and Henrich’s point about groups in competition needing to expel free riders. If you want to imagine a space economy, you could do worse than starting from here.

Notice that Ostrom’s book proves conclusively that “tragedies of the commons” do not always occur. Indeed, the 1968 paper by ecologist Garrett Hardin which introduced the “tragedy” concept was based not on evidence, but on deductive thinking: if homo economicus is a good model for human behavior, then tragedies of the commons should occur. Historically, the English commons (common lands) were eliminated not by “tragedies” of overconsumption, but by violent evictions and enclosures. Hardin himself was a white supremacist who cultivated a “lifeboat” vision of society.

War economies

A war economy is an economy the purpose of which is exogenous to the economy itself. Typically, this purpose is winning a war: the enemy is at the gate, and all economic efforts are directed to defeating them. War economies are field tested, and have proven to work extremely well: the most famous example is that of Germany during World War 1. Germany’s technocrat-in-chief, Walther Rathenau, pivoted the Empire’s economy in a matter of weeks as the war started [Scott 1998]. The state became the master planner, and, for many businesses, the main client and a sort of uber-CEO, with entire conglomerates strongarmed into pivoting overnight into new products.

This move was very successful in keeping the German army in the field and equipped, well after external observers had predicted its dissolution. And it was widely copied, which is why Rolls-Royce makes airplane engines as well as luxury cars.

Red plenty

This is more conjectural: the idea is that, as computing becomes cheaper and more powerful, central planning might emulate the efficiency of markets, while overcoming the latter’s blindness to externalities such as pollution or care work. We do know that the Soviet Union attempted cybernized central planning using linear programming techniques [Kantorovich 1939]. The centerpiece of the effort was the idea to use something called shadow prices (the marginal advantage of releasing a constraint) to simulate market prices. This fascinating story is told in a very strange (history? Fiction?) book by Francis Spufford, Red plenty.

8. Thinking up a fictional economy with subgame-perfect equilibria

In an attempt to grapple systematically with these ideas, a few years ago I was part of a group of people that were interested in the intersection between science fiction and economics, and called ourselves, cheekily, the Science Fiction Economics Lab. We started turning these things around in our heads, and came up with the idea of an open source world where we could explore these thoughts. We were doing worldbuilding, rather than writing actual sci-fi (though eventually some sci-fi stories set in our imaginary world did appear).

The overarching concept was that of a floating megacity, adrift in the oceans of a vaguely post-climate change Earth. We called it Witness. Witness had launched as a unitarian project, inspired by the floating city concept of UN Habitat, but then it had fractured along ideological lines. It was large enough to sustain several splinters, called Distrikts, each of them with its own economic system. We structured the work on Witness as a wiki (Witnesspedia), with major entries for the most important Distrikts: Libria, a hypercapitalist economy with minimal state intervention, reminiscent of much cyberpunk dystopias and, well, us. The Assembly, a cooperativist society with super-strong anti-monopoly culture. Hygge, a Nordic social-democracy on steroids; the Covenant, characterized by the presence of many monasteries and other religious institutions, with a strong manufacturing vocation (pun unintended).

This all is fun, but quite hard to take it down one level, to imagining institutions like markets, central banking, antitrust enforcement agencies, and indicators of economic performance (because, seriously, what kind of self-respecting sci-fi piece of work would still be mentioning GDP?). The incentive compatibility constrain kicks in. Perhaps the hardest nut to crack is the presence of trade across different systems: if Libria can trade freely with Hygge, will not its products – made with alienated labour – outcompete the fairer ones in Hygge? If not, why not? You find yourself designing policies that reproduce the economic systems you want – which is more or less what Graeber and Wengrow tell us real societies do.

In trying to make these imaginary economies credible, we felt the need to come up with an origin story. If these systems are in our future (which makes them more relatable) there should be an incentive-compatible path from here to there. So, maybe a Distrikt in Witness has robust trustbusting policies. Problem with monopolists is that they tend to capture their regulators, because they typically have more money and woman- or manpower than them. So, a society with strong anti-trust policies that never had any large monopoly is in equilibrium, because no firm becomes big enough to capture the regulators. But a society that starts with incumbent monopolies (like we do), and then somehow introduces antitrust policies, is not, because monopolists have the power to prevent effective regulation. To be credible at all, an imagined future needs to be connected to the present by an unbroken series of changes, each of these is incentive compatible. Game theory has a formalization of this concept, called a subgame-perfect equilibrium [Selten 1988].

Subgame-perfection is a test for the believability of the origin story of an economic system. To pass the test, the story needs to respect the incentive-compatibility constrain at each step of the way.

9. Coda: the role of science fiction in developing economic thinking

For the first time since I am intellectually active, late-stage capitalism is being seriously contested; and neoclassical economics with it. The battering ram of these contestations, alas, is not the economics profession, but climate change. But the profession is stirring, flexing muscles that had not been used for almost 100 years. New concepts are afoot: degrowth. Commons-based peer production. Universal basic services. Modern monetary theory. And some old concepts, like mutualism, and cooperativism, are making a comeback. They can inspire you as you build fictional economies in your head, and I hope you have as much fun as I did.

It is fun, but it also is important work. Like Cory Doctorow says, science fiction stories can function as architects renderings, making these models come alive, showing us what our lives would be like, if we lived in these systems. What would our jobs look like on a planet (in a galaxy far far away) that embraced degrowth? Our schools? Our romantic life? I am convinced that we need science fiction to inspire democratic debate on the urgent economic reforms that await. So, let’s get to it.

Essential bibliography

- D. Graeber and D. Wengrow, 2021. The dawn of everything: a new history of humanity. London: Allen Lane.

- J. P. Henrich, 2016. The secret of our success: how culture is driving human evolution, domesticating our species, and making us smarter. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- L. Hurwicz, “Optimality and informational efficiency in resource allocation processes,” in Mathematical methods in the social sciences, K. Arrow, S. Karlin, and P. Suppes, Eds., Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- E. S. Maskin, 2008. “Mechanism Design: How to Implement Social Goals,” American Economic Review, vol. 98, no. 3, pp. 567–576, May 2008, doi: 10.1257/aer.98.3.567.

- M. Mazzucato, 2018. The value of everything: making and taking in the global economy. London, UK: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books.|

- E. Ostrom. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, 1st ed. Cambridge University Press, 2015. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316423936.|

- R. Selten, 1988. “Reexamination of the Perfectness Concept for Equilibrium Points in Extensive Games,” in Models of Strategic Rationality, vol. 2, in Theory and Decision Library C, vol. 2. , Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 1–31. doi: 10.1007/978-94-015-7774-8_1.|

- E. O. Wilson, 2012. The social conquest of earth, 1st ed. New York: Liveright Pub. Corporation.|