I am part of a group which is building a cohousing in Brussels. It’s a risky endeavor but I could just not resist it: I dislike how the real estate market has financialized the right of humans to decent housing, and I dislike how the manner of building homes have made us lonely, alienated, surrounded by strangers. As an economist, I also find modern housing incredibly inefficient, because it does not produce public goods – like common spaces and communities – that are, by definition, the most efficient goods there are. And so, after many years of longing and reflections, in late 2021 I found myself in a small group willing to try it out, and took the plunge. Our cohousing is called The Reef in tribute to the diverse webs of cooperation and competition that exists in real coral reefs, and also as an act of remembrance should all coral reefs in the world die, which is not unlikely at all.

It is an incredibly rich, life-changing experience. It is also the second most difficult thing I have ever done (the first was founding a reasonably successful punk-folk band), and the one with the first-highest stakes (for most of us it is all of our lives’ savings). Yet, I never posted about it before, with one exception at the beginning of the journey. Frankly, I was not sure of what lessons one could draw from it: we were certainly working hard, but were we getting anywhere? Were we on our way to success, or just deluding ourselves? I could not tell. In the legal framework and economic landscape of Belgium in the 2020s, building a cohousing is a highly uncertain affair. At every turn, you face another obstacle that has the potential to stop the entire project dead in its track. Will we find a site to build the cohousing in? Will we be able to work together in reasonable harmony, or will the group collapse under the weight of interpersonal conflict? Is there even enough demand for cohousings to complete a group? Will the war in the East make construction materials unaffordable, and our project with it?

Still, people around me are interested in learning about cohousing. Many have encouraged me to start sharing my reflections about it. And it is the right time: the project has reached a degree of maturity where, I think, we can start drawing some lessons from it – though it could still fail, of course. There is a lot to share, but I am going to start with only few of the clearest learnings so far.

1. Self-managed projects are surprisingly efficient

Over the years, I have spoken to many people that dream of living in a cohousing. Despite this, it is almost impossible to just go out and buy a house or an apartment that is part of one. There appears to be what economists call a market failure: there is a market demand for a more social way of living, but no supply. So, if you want to live in a cohousing you will most likely need to start a group, or join one, and have your cohousing built to specifications. Groups must make a choice as to how to organize themselves. One possibility is for the group to directly take charge of the project management: find a site to buy, negotiate with the owner, purchase it, hire an architect and a construction company, organize the financial flows and so on. The other is to hire a company that will take care of the project management for you. In Belgium we are fortunate that there exist two such companies.

The Reef chose to be a self-managed group. In practice, this means that a bunch of random people, none of whom is a real estate or construction professional, is now running a 9 million Euro real estate project. Counterintuitively, this is working better than we had any right to expect: processes are transparent and relatively fast. We learned to work as a team quite quickly, and there is a high level of accountability. The Reef is a healthier, more efficient working environment than many professional spaces I have worked in. We have to work harder, but that work will pay for itself in terms of added trasparency and fuller ownership of the project. There is pride and joy in working together as a group to build our future home, and we believe that doing it this way will make our little community even more cohesive – and we save money.

2. Building community comes natural

Most people in our group did not know each other before joining. Most of us joined not based on previous friendships or family ties, but because we are drawn to the idea of cohousing itself. Some of us thought this might pose a challenge: in this kind of project people are making large investments in an endeavor the outcome of which depends on their cohousing mates playing nice. A lot of trust is needed. Among the many challenges of cohousing, this one turned out to be fairly easy. Common involvement in this kind of project builds mutual trust, even friendships, relatively quickly. This is because the project itself gets you into repeated interactions with each other. Reputation is obviously valuable, so people do not like to drop the ball on one another. In a short time, you realize you can trust these people after all, and start to relax and enoy their company. I have no doubt that The Reef will be an imperfect but functional, and even beautiful, community.

3. Process and information tidiness are critical

In 2021, as a prequel to the formal start of the process of building The Reef, the founding group spent a few months researching cohousing. We read up on everything we could find, and engaged with extant cohousing groups to learn from their experiences. We also arranged to visit several already-built cohousings. All sources pointed to how critical good process is.

The reasoning is straightforward. Building a cohousing takes 4-7 years. During this period, you will be doing weekly meetings plus individual- or small-group work. All of this effort is unpaid, and you will still have all of your personal and professional responsibilities. You might even be asked to step up a little to cover for your cohousing mates: for example, in our group parents of small children are given a pass, and just asked to respect the deadlines and otherwise do what they can, no questions asked.

In a situation like this, it is super important to be methodical and efficient, or you will become overwhelmed. The Reef is very methodical, on two fronts. First, we are organized according to a variant of a model called sociocracy. This means plenaries + teams that report to the plenary and do the heavy lifting of preparing the decisions for the plenary to take. All meetings are facilitated (by a Team Facilitation, whose members took trainings in sociocratic methods). The entire group took trainings in non-violent communication as a measure to prevent the escalation of conflicts. This method is very efficient, and it saves time on decision making that we sorely need for operations. For example, while searching for a site we scouted the entire city on bicycles and on foot for six months, mapping and evaluating 170 potential sites. Even with a fairly large group of a dozen active adults, you see why efficiency is so important.

Second, we take information management seriously, and adopted ways inspired by the open source and open knowledge movement. All information is public by default, and protected only if there is a need for confidentiality. A very successful move was to ban emails completely, and instead move our communication onto an online forum. This reduces Inbox stress and allows people full access to every communication, letting them choose what they want to engage with. It also makes past communications very searchable (we even use tags consistently, something that I have not experienced in any other working environment). Do not underestimate the impact of using good forum software over email – let alone stuff like Facebook or Whatsapp or Slack groups, which is not, repeat not, optimized for economical and accountable communication! Our forum as of now hosts over 10,000 messages, and has over 300,000 pageviews, and the fact that it allows access while not flooding us with notifications is valuable. Transparency is also important

From open source culture we also learned the importance of good documentation: for example, we have a guide to The Reef’s digital assets, one to using tags and groups in the forum, one to making changes to the website, a manual to onboard new members, a governance document. Each one of these shares knowledge and empowers everyone in the group, removing organizational bottlenecks, at the cost of having to write things down in a clear and accessible format.

4. A cohousing ecosystem is coalescing in Brussels

Self-managed groups like ours need not be navigating uncharted waters all the time. To our surprise and delight, cohousing is something like a movement. People support each other, mostly with information that can save us enormous amount of time. The advice we received from our sister cohousings at the beginning of the journey was invaluable. Also, there are now a few professionals in Brussels that understand cohousing and have experience of building them: the architects’ studio Stekke and Fraas has already built three cohousings in Brussels; Mark Van den Dries, a retired entrepreneur that has led several successful cohousing projects (he lives in one) and now offers himself as a coach; the Namur notary Pierre-Yves Erneux. A Dutch-Belgian bank, Triodos, offers mortgages adapted to the reality of cohousing.

All this means that we have it much easier than first-generation cohousings. Like all economic movements, cohousing is cumulative: if you were to start a project now, you would face fewer uncertainties than we did, because you could build on our experience. And if you or someone you know did start a cohousing, I would be interested to learn about it, be it through a link you share or by sharing war stories over coffee.

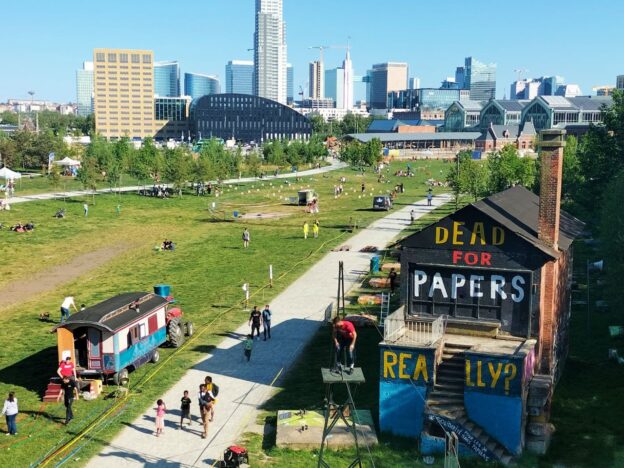

Photo: The Reef’s group explore a candidate site for the cohousing project in summer 2024. CC-BY The Reef Cohousing