The campaign for this year’s municipal elections in Milan left us with a precious legacy: the awareness that many citizens are willing and able to collaborate with their elected representatives in a constructive way. Thanks to the large number of people involved, their great creative energy, and their Internet tools to coordinate towards common goals, the connected citizenry’s potential to contribute to a much needed general renewal of the country is out of the question. The Italian civil society claimed a role for itself; there was no Obama to summon it. As it turns out, it has proven to be at least as advanced as any other in the world, and possibly more so.

This legacy, it turns out, has a dark side. Besides citizens, the protagonists of the Milanese campaign were Internet communication experts, who tend to have a marketing background. The marketing-derived approach makes sense for election campaigns, because voting has near-zero cost; low thresholds for access; and above all is often driven by non-rational, gut feeling motivations. All of these characteristics carry through to the purchase of consumption goods. So, political communication experts speak the language of marketing and advertising: they tell stories like Nixon losing the presidency to Kennedy because, in the key TV debate, he was sweating. Their job is not to help the citizenry to build a realistic idea of what is needed in the next term, but cajole them into voting for a certain candidate, even if they do it for superficial or wrong reasons. Granted, it is not particularly noble, but it works.

Collaboration between citizens and public authorities is very different from competition for votes, and the analogy with purchase of consumption goods does not carry through. Designing and enacting policies is a high-cost, prolonged activity; it requires rational argument, data, competence. In this context the marketing profession’s seduction techniques don’t work well; what’s more, they risk doing damage. In particular, they risk creating participation bubbles: initially luring into signing up people that later, faced with the exhausting wrangle of designing policy, get disheartened and defect en masse – leaving themselves with a bad experience and others with the chore of reorganizing the whole process. Enacting the wiki government is not about attracting large crowds, but about enabling each and every citizen to choose whether to engage, and just what with, while giving her honest information about the difficulties, the hard work, the high risk of failure associated with participation. Indicators, too, have different meaning than in marketing: in the advertising world attracting more people is always better, whereas in the wiki government there is such a thing as too much participation (it entails duplication of information, with many people making the same point, and reduction in the signal-to-noise ratio, with low-quality contributions swamping high-quality ones).

There is a fundamental difference in the way the decision to engage is modeled: in wiki-style collaboration participants self-select, in marketing the communication experts selects a target in a top-down way. In the former the participant is seen as a thinking adult, that needs to be enabled and informed so that she can make the right decision; in the latter the consumer (or voter) is seen as a stupid, selfish individual that reacts to gut stimulation, and that needs to be led to do what we know must be done. The outcome of collaboration, when it is well designed, is open and unpredictable; the outcome of marketing, when it is well designed, is meeting some target set a priori.

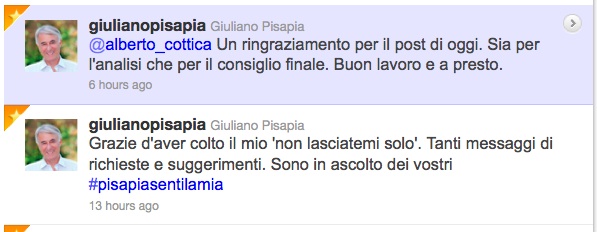

All in all, a shift towards marketing of the discourse on collaboration would be a mistake. An increase in the number of participants to a single process does not automatically mean an improvement; a mayor is not a brand; a willingness to help out is not a trend to be exploited on the short run (and if it is we have no use for it, because collaboration on policy yields results on the medium to long run); and above all citizens are not a target, because they don’t need to be convinced: they need to be enabled to do whatever it is they want to do. It is crystal clear that Italians are up for trying out a collaboration with any half-decent public authority; this collaboration needs space and patient nurturing to grow healthy and strong, sheltered from hype and unrealistic expectations. I hope that the leaders of Italian authorities – starting from the new mayor of Milan Giuliano Pisapia, the leader who best synbolizes the current phase – resist the temptation to frame collaboration as a campaign, citizens as voters, rational conversation as hidden persuasion. Yielding to it would mean shooting themselves in the foot, and wasting an opportunity that the country cannot afford to miss.