Ho a cuore le politiche pubbliche, e cerco di contribuire al loro miglioramento. Sto esplorando l’Internet sociale come strumento per collegare i cittadini tra loro e alle istituzioni, analizzare i problemi di governance, progettarne soluzioni e realizzarle – il tutto in modo decentralizzato. Ho scritto un libro per mostrare che è stato fatto, e argomentare che si dovrebbe farlo più spesso.

Non è una discussione facile. Molti decisori rimangono scettici: cosa ci garantisce che la discussione online converga verso un consenso basato su argomenti razionali e dati empirici? Un ristretto numero di persone con un metodo di lavoro comune possono formare un gruppo efficace, ma grandi masse di cittadini diversi tra loro e autoselezionati sono destinate a crollare sotto il peso di controversie, trolling e puro e semplice sovraccarico informativo. Abbiamo esempi di casi in cui questo non è successo, ma non abbiamo una teoria a guidarci nella progettazione di ambienti per la conversazione che producano i risultati voluti. Non è abbastanza.

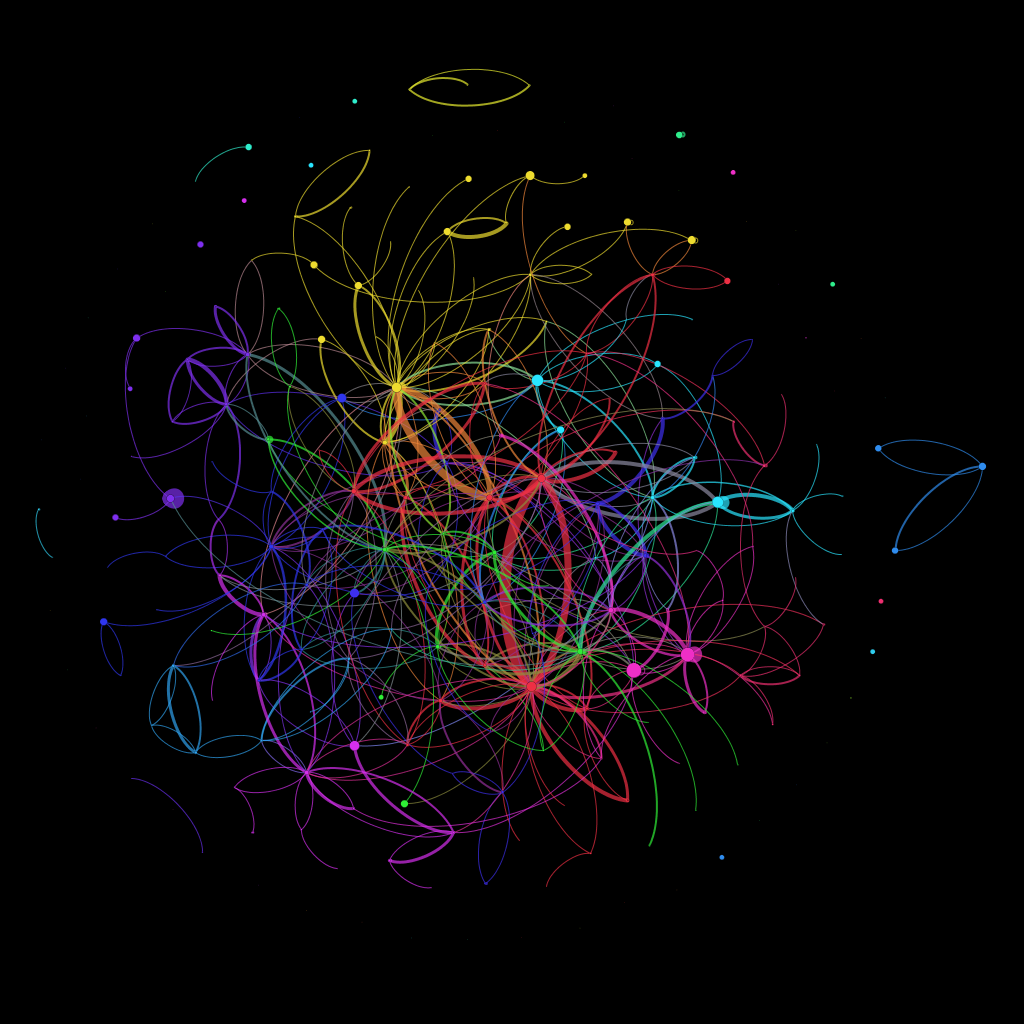

Recentemente ho fatto un po’ di ricerche che potrebbero aprire uno spiraglio. Si tratta di un’analisi di rete della conversazione su Edgeryders. L’ho scritta in inglese – la trovate qui sotto. Per chi non legge l’inglese ma fosse interessato: non esitare a metterti in contatto con me, è facile trovarmi in rete (basta anche lasciare un commento qui). Nel video qui sopra (anch’esso in inglese) si trova un’analisi più dettagliata dei dati e una visualizzazione carina della crescita della rete.

How online conversations scale, and why this matters for public policies

I care about public policies, and try to contribute to their betterment. The road I am exploring is to take advantage of the social Internet to connect citizens among themselves and with government institutions to assess governance problems, design solutions and implement them – all in a decentralized fashion. I wrote a book to show it has been done, and to argue for it to be done more.

But it remains a tough sell. Many decision makers remain skeptical: why should online conversations converge onto evidence-based consensus? A few people who share a common work method can make an effective group, but a large number of very diverse and self-selected citizens – what I have been arguing for – is likely to collapse under the weight of trolling, controversy and sheer information overload. We have examples in which this did not happen: but we don’t have a theory to guide us in designing conversation environment which produce the desired results. Not good enough.

Some work I have been doing recently might provide a lead. As the director of Edgeryders, I marveled at the uncanny ability of that community to process complex problems – as I had done many times before in my years as a participant to online conversations. But this time I had access to the database, and – together with my colleagues at the Council of Europe and the Dragon Trainer project – I used it to reconstruct a full model of the Edgeryders conversation as a network. The network works like this:

- users are modeled as nodes in the network

- comments are modeled as edges in the network

- an edge from Alice to Bob is created every time Alice comments a post or a comment by Bob

- edges are weighted: if Alice writes 3 comments to Bob’s content an edge of weight 3 is created connecting Alice to Bob

I looked at the growth over time of the Edgeryders network as defined above, by taking nine snapshots at 30 days intervals, working backwards from July 17th 2012. For each snapshot I looked at four parameters:

- number of connected components (“islands” in the network)

- Louvain modularity of the network. This parameter identifies the network’s subcommunities and computes the difference between its subcommunities structure and what you would expect in a random network. Modularity can take any value between 0 and 1: higher values indicate a topology that is unlikely to emerge by chance, so they are the signature that some force is giving the network its actual shape; low values mean that the breakdown into subcommunities is weak, and could well have emerged by chance.

- for modularity values indicating significance (above 0.4), the number of subcommunities in which the network is broken down by the Louvain algorithm

These indicators for Edgeryders agree that there is no partitioning in the network. All active members are connected in one giant component, whose modularity values stay consistently low (around 0.3-0.2) throughout the period analyzed. This is not surprising: my team at Edgeryders had clear instructions to engage all newcomers into the conversation, commenting their work (and therefore connecting them to the giant component). From a network perspective, the job of the team was exactly to connect every user to the rest of the community, and this means compressing modularity.

Next, I looked at the induced conversation, the network of comments that were not by nor directed towards members of the Edgeryders team. It includes conversations that the Council of Europe got “for free”, without involving paid staff – and in a sense the most diverse, and therefore the most interesting. To do this, I dropped from the network the nodes representing myself and the other team members and recomputed the four parameters above. Results:

- there is a significant number of “active singletons”, active nodes that are only talking to the team members, but not to each other. This might indicate a user life cycle effect: when a new user becomes active, she is first engaged by a member of the paid team, who tries to facilitate her connection to the rest of the community (by making introductions etc. My team has specific instructions to do this). The percentage of active singletons decreases over time, from about 10% to less than 5%.

- not counting active singletons, there are several components in the induced conversation network. A giant component emerges in February; from that moment on, the number of components is roughly constant.

- the modularity of the induced conversation network (excluding singletons) is high throughout the observation period (over 0.5),

- the modularity of the giant component is also high throughout the period (over 0.5). Interestingly, modularity grows in the November-April period, indicating self-organization of the giant component. In February it crosses the 0.4 significance threshold

- the number of subcommunities in which the Louvain algorithm partitions the giant component also grows over time, from 3 in April to 11 in July

Subcommunities are color coded. Knowing Edgeryders and being part of its community (and having access to non-anonymized data), I can easily see that some of those subcommunities correspond to subjects of conversation. For example, the yellow group in the upper part of the graph is involved in a web of conversation about the Occupy movement and how to build and share a pool of common resources. Also, looking at the growth of the graph over time, subcommunities seem to grow sequentially more than simultaneaneously. This might be related to the management structure of Edgeryders: we launched campaigns (roughly one every four weeks) to explore broad issues that have to do with the transition of youth to adulthood. Examples of issues are employment/income generation and learning. So, an interpretation could be this: each campaign summoned users interested in the campaign’s issue. These users connected to each other in clusters of conversation, and some of them act as “bridges” across the different cluster, giving rise to a connected, yet highly modular structure. The video above has some nice visualizations of the network’s growth and of the most relevant metrics.

This looks very much like parallel computing (except this computer is made of humans), and could be the engine of scalability. As more people join, online conversation does not necessarily become unmanageable: it could self-organize into clusters of conversation, increasing its ability to process a certain issue from many angles at the same time. Also, this interpretation is consistent with the idea that such an outcome can be helped by appropriate community management techniques.

Ten years ago, Clay Shirky warned us that communities don’t scale. He was right, by his own definition of community – which is what in network terms is called a clique, a structure in which everybody is connected to everybody else. I would argue, however, his definition is not the most appropriate to online communities. Communities do scale, by self-organizing into structures of tight clusters only weakly connected to each other.

If we could generalize what happens in Egderyders, the implications for online policies would be significant. It would mean we can attack almost any problem by throwing an online community at it; and that we can effectively tune how smart our governance is by recruiting more citizens. appropriately connected, into it. We at the Dragon Trainer project are following this line of investigation and developing tools for data-powered online community management. If you care about this issue too, you are welcome to join us onto the Dragon Trainer Google Group; if you want to play with Edgeryders data, you can find them on our Github repository.

Coming soon: posts about conversation diversity and community sustainability based on the same data.