Imagine you are in Hamburg for 30C3, the thirtieth annual conference of the legendary Chaos Computer Club – the first and the largest association of hackers in Europe. Uncharacteristically, you are being engaged in politics: you take part in a meeting convened on the fly by Ásta Helgadóttir, a young activist of the Icelandic Pirate Party. The person speaking now is Amelia Andersdotter, a 26-year old Swede, Member of the European Parliament, also a Pirate. She explains that the European Commission is considering a reform on copyright law, and that such reform is at risk of damaging the Internet’s freedom and wholeness. The Commission has recently launched an online public consultation, but taking part in it is so difficult and time-consuming that activists fear only the copyright industry’s professional lobbyists will end up participating in it.

Andersdotter and her staff, helped by many volunteers, have compiled a on online guide to the consultation available in 13 languages, but this is not good enough. For everyone to be able to participate, it is critical that participation is made much easier and more intuitive.The group decides to achieve this building a website that starts from the friction with copyright law experienced by citizens on the web every day encoded in user stories (for example: “I don’t dare to make a remix because of fear of repercussions”). From there, the website guides citizens to share their points of view on these small daily conflicts, and inserts their reflections in the questionnaire as appropriate. All is left to do is for the citizen to download the completed questionnaire and e-mail it to the Commission.

As the meeting ends, a task force of coders and designers fires up their laptops and goes to work. For starters, Stefan Wehrmeyer from Open Knowledge Foundation Germany writes the core code for the new website, and uploads it on a GitHub repository (a familiar collaboration platform for open source programmers) for everyone to be able to contribute. Next, Mathias Schindler from Wikimedia Germany rewrites the questionnaire’s questions in terms of situations that are easy to map onto normal experience of the web. Finally, Juliana Okropiridse, Bernhard Hayden, Christopher Clay and Peter Grassberger of the Austrian Pirate Party kickstart a hackathon to finish the website. Hosted by (Viennese hackerspace) Metalab’s assembly at 30C3, they code all night long. At 8 the next morning, copywrongs.eu is online. The date is December 30th, 2013.

All this has really happened.

How did we get there? How does a fairly technical legal issue like the reform of European copyright law get to be debated, and eventually acted (and hacked) upon, in a hacker conference? To understand this, we need to take a step back.

On December 5th 2013 the European Commission launched an online consultation on copyright law reform in Europe. In the digital age, copyright law has become a contentious issue: adapted to broadcast technologies (printing press, radio and television), it ended up clashing with the Internet’s technological and social infrastructure. Network technology allows to make fast, inexpensive and exact copies of any content (books, music, films, scholarly articles etc.) and to spread them across the planet at the speed of light. On top of that, it allows – and sometimes requires – to do things that have no exact equivalent in the pre-digital world, like linking, caching, or remixing them. Are these things legal? Under which conditions? Predictably, netizens ended up wondering why would these operations – useful, simple, cheap – not be allowed; and digital native teenagers across the globe engaged in them with gusto.

Copyright holders reacted aggressively to what they think is an infringement of their rights. They demanded and obtained from lawmakers harsher penalties for copyright infringement (especially in the USA), and consistently sued young people, even minors, for lots of money – probably trying to scare off other infringers by gunning for some. The debate heated up. Exactly a year ago, on January 11th 2013, Reddit co-founder and hacktivist Aaron Swartz took his own life at 26 years of age. He was facing prosecution for copyright infringement – he had downloaded a large number of copyrighted scholarly journal articles, using his access as a MIT student).

Copyright is important, and the opening of the European Commission’s consultation could be good news. But there is a problem. The consultation consists in a questionnaire to download, fill and email to the Commission. The questionnaire is available in English only; takes several hours to complete (it is 36 pages long and consists of 80 questions); is written in legalese; and the window for doing all this is only 60 days, including the festivities break [yielding to requests from citizens, the deadline has now been moved 28 days forward to March 30th].

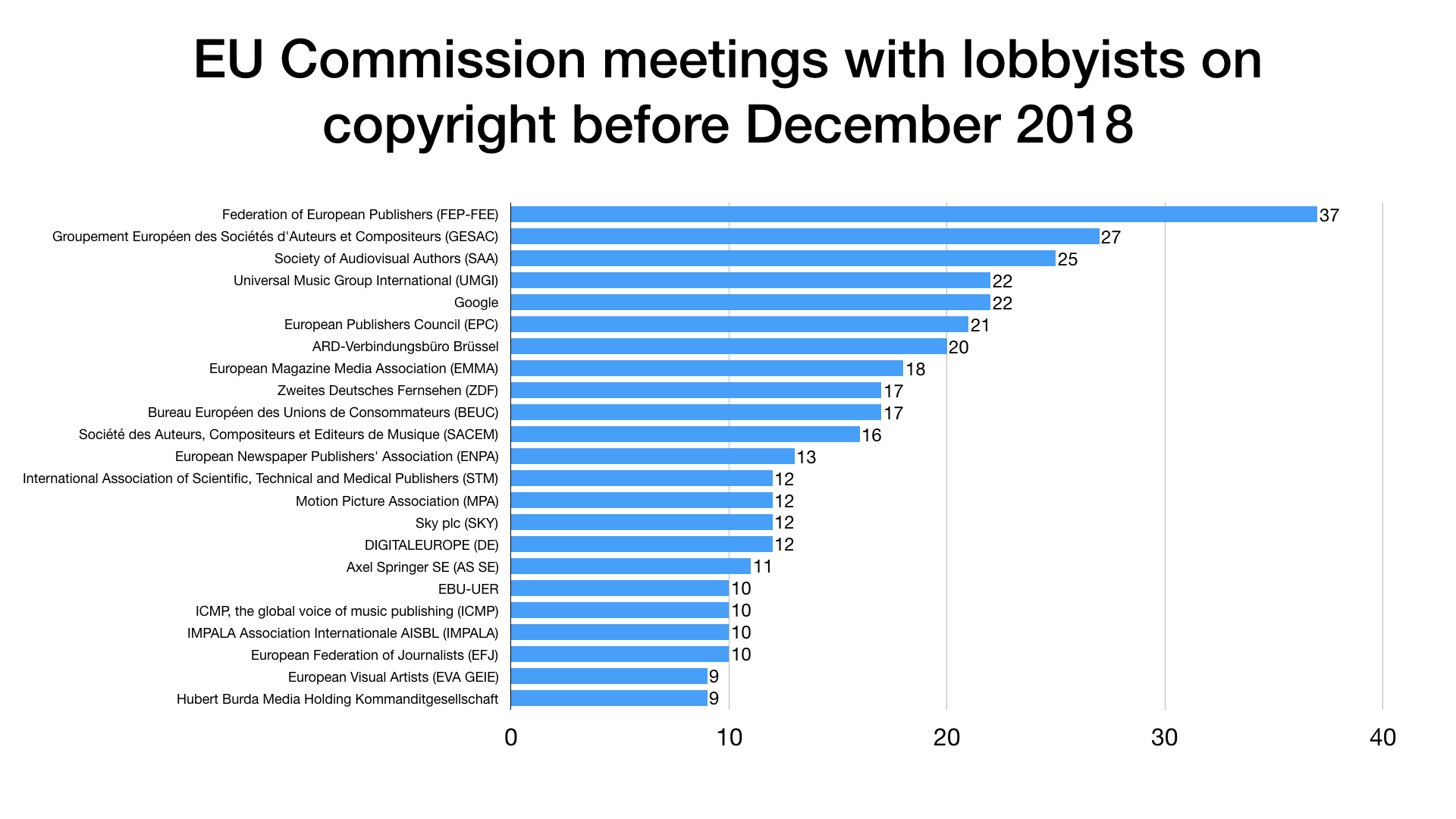

What sort of citizen do the designers of this consultation have in mind? I can think of only one type of person that fits it: professional lobbyists working for the copyright industry – record labels, movie production companies etc.. Lobbyists are fluent in English; know well the regulation they are trying to influence; and have no problem finding the time to fill a 80-questions questionnaire, since they – unlike most of us – get paid for it.

There is nothing wrong with a lobbyist stating an opinion in the context of an online consultation. But it is wasteful: lobbyists already have their channels. They have Brussels offices, industry conferences, money to hire consultants and experts and deploy them towards their goals. A public consultation – especially one that uses a pervasive channel like the Internet – could and should go the extra mile to enrich the debate, involing a number as high as possible of ordinary citizens.

Why has this not happened? According to Andersdotter, the Directorate General for the Single Market (DG MARKT) keeps a low profile to eschew controversies and conflicts – but in vain, since these are inevitable. “European citizens are in constant tensions with copyright law – says Andersdotter – For example, it is common for teachers of foreign languages to play DVDs or music CDs as a way to make their teaching more engaging, even if they bought them privately [editor’s note: yes, it is illegal]. Or it may happen that a French citizen shares a music video on YouTube with a German friend, but the latter cannot view it because French right holders have a deal with YouTube and German ones don’t. Many Europeans, especially young, have problems like these.” And it’s not just teenagers: in May 2013 LIBER, the European association of research libraries, walked on DG MARKT’s stakeholder dialogue initiative, claiming that “the research and technology communities have been presented not with a stakeholder dialogue, but a process with an already predetermined outcome” (source). The office of the Single Market commissioner Michel Barnier has not replied to our request for comments.

What can we learn from this story? I think there are three important conclusions.

The first one: online consultation risk playing an antidemocratic role. They can be presented as a gesture of openness and transparency (“it’s on the Internet! Anybody can join in!”) but in truth offer only a new participation channel for interests already represented – a sort of Dark Side of online participation. To prevent this, citizens would do well to demand from their institutions not just to be consulted, but that consultations are designed to maximize participant diversity.

The second one: citizens can play a role in making them better. In the case in point and in other similar ones (remember ACTA?) a smart, tech savvy civil society mobilized to protect a global common, the freedom and health of the Internet ecosystem. Such instant, liquid mobilization produced longer-lasting organizations like Wikimedia and Open Knowledge Foundation, and meeting places like 30C3. Online participation has its Dark Side, but it also has a few Jedi Knights.

The third one: the political space opened by these movements is natively international. Hackers, as no politically relevant group before them, collaborate across state frontiers in a natural, unassuming way. The project to democratize the European consultation on copyright involved people of many nationalities, without anyone ever feeling the need to refer to the positions of one country or another. Interestingly, leadership tends to be allocated to young women like Helgadóttir (23, deputy member of the Icelandic parliament) or Andersdotter herself.

I am fascinated by Andersotter’s trajectory. Elected when she was only 21, she proved incredibly determined, acquiring an impressive competence on international conventions and treaties regulating the Internet in Europe and becoming a reference point for the continent’s open source movement, as well as for the hacker scene in general. She has held her (well documented) ground in favor of Internet freedom, and has not shunned conflict when conflict was in order. She does her best to make the European Parliament more open and welcoming for hackers and activists – for example, she organized a screening of the film about Wikileaks We steal secrets and made it open to the public. Hackers and activists across Europe reciprocate with an almost palpable affection, as if she were – after Lady Ada Byron – a second Queen of the Machines. She could be the first of a new breed of digital native European leaders, grown up between hackathons and The Big bang Theory reruns.

The story I told at the beginning of this post looks more like a scene from Matrix than a story of European politics. And yet, when you think about it, this is exactly the European Union that the founding fathers dreamed of: hackers, designers, civil society activists, elected representatives collaborating across all countries to broaden the channels of democratic participation on the Union’s policies. If I could offer a word of advice to the next Presidents of the European Commission, Parliament and Council I would tell them: fly close to the hackers, involve them, ask them to help you design the Union’s online consultations. They are building the European agora that you could not give us. And – frankly – their code is vastly better than yours.