“Data are the new oil”. Technical advances in computing and a pervasive social Internet make vast datasets on human behavior – as well as the tools to process them – available for cheap. Trouble is, democratic institutions don’t look like they are ready to tackle the big data challenge and the many thorny issues it brings about (privacy, anyone?). They risk playing a distant second fiddle to large hi-tech corporates. Last Friday I shared some musings along these lines at the Future Data conference, held in Florence by initiative of the Italian local authorities’ statistics society (thanks for inviting me!). I was busy with the RENA Summer School in Matera, so I had to send a video. It’s in Italian, but I plan to do more work in English around this.

Tag Archives: dati

The quantified man: from a half marathon to body hacking

Since about a year I have been running somewhat regularly. I started just to have an alternative to the gym when I am on the road, but my motivation have gotten deeper since. Running opens a door on a new and interesting path, not just for me but for all of us.

Here’s the thing: running generates data. A lot of data. Data about us. And we consume them, with ever-growing appetite.

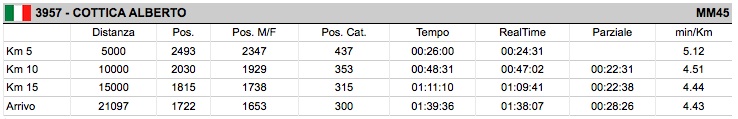

Consider, for example, the Stramilano half marathon, which I run just Sunday. Its over five thousand participants were possibly the most technology-enhanced large group I have ever been part of. Each runner bears a number tag which incorporates a transponder; combined with the sensors scattered along the route and a precise chronometer, this enables very precise tracking of the bearers’ performance. Here is mine:

There is a lot of information in this table. Not just my final absolute- and category placement; not just my official (from start to finish) and real (from the moment when I crossed the starting line to when I crossed the finishing one) time; but all of these, plus cumulated average speed, at four different checkpoints 5, 10, 15 from start and at finish. As you can see, I had a few problems in the early stages, with a low average speed of 5’12″/km (I got stuck behind a phalanx of slower runners). Then it got better: my average speed increased to 4’30” for the following ten kilometers, then decreased slightly again for the last six. At the start I had probably some 4,000 runners in front of me; after 5 kilometers I still had 2,500; in the last sixteen kilometers I overtook almost 800 more. My worst mistake was not try to get further towards the front of the starting grid; this cost me something like two minutes of rel time and three on official time.

But this is just half the story. Practically every athlete in there was equipped with some form of data generation and monitoring: GPS units in their pockets, accelerometers inside their shoes, heart rate monitors on their chests, chronographs on their wrists. Data were processed locally and fed back to the runners in real time; after the race they were downloaded on massive cloud computing systems and processed again to keep track of progress and programme future training. I, for one know full well that I have run 609,17 km since late July 2010. It took me 51 hours, 3 minutes and 3 seconds, at an average speed of 5’03″/km and burning 39.305 calories. I know absolutely everything.

This knowledge gives me control. The data, once processed and interpreted, make us faster. Athletes with a little experience use them to decide on competition strategies. If you run in large groups, you’ll hear beeps and alert going off at every turn, and it is not uncommon to hear remarks like “we are ten seconds late on our flight plan”. The Stramilano crowd was running amidst a cloud of computation.

Running is just an example of a general trend towards an ever-increasing computational density of our lives. We monitor, record and quantify our trips, our social and professional networks. More and more often we do the same for our physical existence, tracking metrics like weight, glucose levels, body fat. We sequence our DNA. For each of these metrics, be they social or physical, we have online services that allow us to share them with others and turn them into conversation topics (and we do it, not overly concerned with privacy). Americans talk of “quantified self”: it is a rapidly growing movement, because data allow us to explore how our bodies react to different stimuli, and adjust our behaviour accordingly. If I discover that a certain training routine improves my performance, or a certain diet lowers my body fat, I can use them to meet my goals in terms of running, or just looking good. If I quantify my body, it becomes easier to hack it.

The word “hacking” in this context is exactly right. Like the original hackers, body hackers are outsiders to the system, so they can afford to be radical. Like Tim Ferriss says: “I am neither a doctor, nor a Ph.D. I don’t have a publish-or-perish career. I can test hypotheses using the kind of self-experimentation mainstream practioners can’t condone. By challenging basic assumptions, it’s possible to stumble upon simple and unusual solutions to long-standing problems”. Spoken like a true hacker. In other words, I teach myself some knowledge, then I use a low-access technology to tinker around. When enough people do that, open innovation happens.

The Stramilano half marathon was a wake-up call: self quantification is becoming a mass phenomen. Expect a wave of open innovation, and a new generation of hackers. But this time it will be our own bodies acting as both labs — and prototypes.

L’uomo quantificato: dalla mezza maratona al body hacking

Da circa un anno corro con una certa regolarità. Ho iniziato per avere un’alternativa alla palestra che posso portare con me quando viaggio, ma adesso le mie motivazioni sono molto più profonde. La corsa ha aperto una porta su una strada nuova e interessante, che non riguarda solo me ma tutti noi.

Il fatto è questo: correre genera dati. Molti dati. Dati su di noi. E noi li consumiamo, con un appetito che cresce continuamente.

Considerate, per esempio, la mezza maratona della Stramilano, che ho corso domenica. Gli oltre cinquemila partecipanti costituivano forse il gruppo di grandi dimensioni più accresciuto dalla tecnologia a cui abbia mai partecipato. Nel pettorale con il numero di gara è inserito un transponder; combinato con i rilevatori sparsi lungo il percorso e un cronometro preciso, questo permette di tracciare in modo molto preciso la prestazione di chi lo porta. La mia è questa:

Ci sono molte informazioni in questa tabella. Non solo la mia posizione in classifica assoluta e per categoria; non solo il mio tempo ufficiale (dal momento del via al traguardo) e quello reale (dal momento in cui ho attraversato la linea di partenza all’arrrivo); ma tutte queste variabili, più la velocità media cumulata, rilevate su quattro tronconi del percorso (da 0 a 5 km; da 5 a 10; da 10 a 15; da 15 a 21,097). Come potete vedere, ho avuto problemi all’inizio, con una velocità media piuttosto bassa: 5’12″/km (sono rimasto imbottigliato dietro corridori più lenti di me). Nei tratti successivi, però, mi sono in parte riscattato: la mia media è scesa a 4’30” per i successivi dieci chilometri, per poi risalire a 4’39” agli ultimi sei. Alla partenza avevo probabilmente quattromila persone davanti; al quinto chilometro ne avevo ancora duemilacinquecento; nei sedici chilometri successivi ho superato quasi ottocento corridori. L’errore più significativo che ho fatto è stato di non cercare di portarmi più avanti nella griglia di partenza; probabilmente questo mi è costato due minuti sul tempo reale, e tre su quello ufficiale.

Ma questa è solo una parte della storia. Praticamente tutti i partecipanti alla gara si erano attrezzati con proprie forme di rilevazione ed elaborazione di dati: GPS in tasca, accelerometri nelle scarpe, fasce con cardiofrequenzimetri intorno al torace, cronometri al polso. Vengono elaborati in locale e restituiti al corridore in tempo reale (il mio iPod mi segnala distanza percorsa, tempo di percorrenza e velocità istantanea). Poi vengono scaricati su sistemi massivi di cloud computing ed elaborati di nuovo, per programmare gli allenamenti e tenere conto dei progressi. Io, per dire, so esattamente che, da fine luglio 2010, ho percorso 609,17 km di corsa in 51 ore, 3 minuti e 8 secondi complessivi, a una velocità media di 5’03″/km, consumando 39.305 calorie. Ho traccia di ogni allenamento. So assolutamente tutto.

Questa conoscenza mi dà controllo. I dati, rielaborati e interpretati, ci rendono più veloci. Gli atleti con un minimo di esperienza li usano per impostare strategie di gara. Se corri in grandi gruppi, senti congegni di ogni tipo trillare in continuazione, e non è raro sentire corridori dirsi cose come “siamo dieci secondi in ritardo”. La folla della Stramilano ha correva avvolta da una nuvola di computazione.

La corsa è solo un esempio di una tendenza generale verso l’aumento della densità computazionale delle nostre vite. Monitoriamo, registriamo e quantifichiamo i nostri spostamenti, le nostre reti sociali e professionali. Sempre di più facciamo lo stesso per il nostro corpo fisico, tenendo traccia di metriche come il peso, il tasso glicemico, la percentuale di grasso sulle masse corporee. Sequenziamo il nostro DNA. Per ciascuna di queste metriche, fisiche o sociali, sono disponibili uno o più servizi online che ci consentono di condividerle e di farne argomenti di conversazione. Gli americani parlano di “quantified self”, del sè quantificato. È un movimento in via di rapida diffusione, perché i dati ci consentono di esplorare come il nostro corpo reagisce agli stimoli più diversi, e comportarci di conseguenza. Se scopro che un certo tipo di allenamento migliora le mie prestazioni, o che un certo tipo di dieta mi fa perdere rapidamente grassi, posso usarli per raggiungere i miei obiettivi di prestazioni o di percentuale di grasso corporeo. Se quantifico me stesso, posso modificarmi. La disponibilità di dati e capacità computazionale apre la strada per il body hacking.

La parola “hacking” in questo contesto ha tutti i significati al posto giusto. Come gli hackers originali, anche i body hackers sono abbastanza esterni al sistema da potersi permettere di essere molto radicali. Come dice Tim Ferriss: “Non sono nè un medico nè uno scienziato. La mia carriera non mi richiede di pubblicare per forza. Posso testare le mie ipotesi su me stesso, con metodi che medici e scienziati non possono rischiare. Mettendo in discussione le ipotesi di base, posso scoprire soluzioni semplici e insolite a problemi resistenti.” È esattamente un discorso da hacker: acquisisco una formazione da autodidatta su un argomento e uso una tecnologia di facile accesso per smanettare. È il presupposto dell’innovazione aperta.

La Stramilano per me è stato il primo segnale che la quantificazione del sè fisico sta diventando un fenomeno di massa. Aspettatevi un’ondata di innovazione aperta, e una nuova generazione di hackers. Ma stavolta saranno i nostri corpi a fare da laboratori — e da prototipi.