With the Living On The Edge (aka #LOTE) conference, the Edgeryders team at the Council of Europe was trying to kill several birds with the same stone. Bird number one: starting to boil down the staggering amount of ethnographic data on the transition of European youth collected alongside the project to a synthesis that could act as a common ground. Even before the conference started we had collected over 400 transition stories with 3,000 comments from over 1,000 registered users: an overarching big picture to parse them is a must if we are to make sense of it. Bird number two:experimenting offline with the delicate interface between online communities and institutions. Can we design a format that Europe’s most radical and bright trailblazers and its civil servants can both find meaningful and fulfilling? Bird number three: gauge the potential for contagion of cutting-edge projects like Edgeryders with the institutions that promote them – but then need to give up some control over them to their community of users if they are to be successful at all. Will institutions experience some kind of anaphylactic shock and reject the transplant? Ignore it? Be inspired by it?

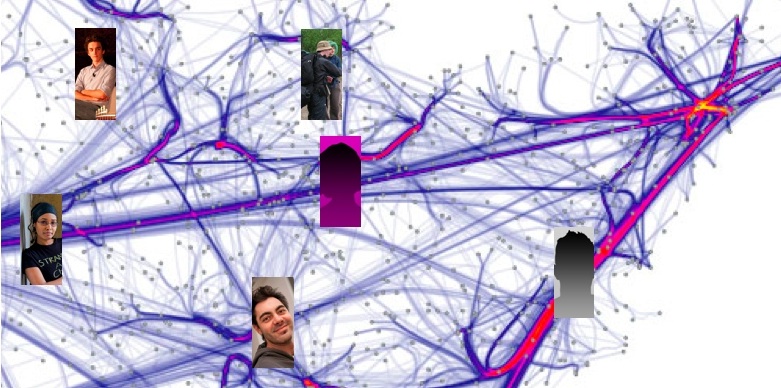

Killing bird number one was comparatively easy: we had aimed very carefully. We designed Edgeryders with native support for scientific inquiry. The legal infrastructure is such that all deliverables from the project are licensed in Creative Commons-BY, and therefore can be shared and re-used legally and safely. A volunteer Privacy Manager from the community, neodynos (thanks!), watches that we do this without compromising the sense of safety that a public space like Edgeryders should have. We extract data from the network analysis directly from the database, via a Drupal module called Views and an extraction script (thanks Luca Mearelli, my collaborator at the Dragon Trainer project, for writing it!). Both the script and the anonymized data are on github. We are proudly doing open science here. So, the rest is really just implementation.

Bird number two was hard. As we designed the conference program, I will freely admit it did feel contrived at times. Luckily my colleagues at the Council of Europe – and especially Gilda Farrell, the head of the division I report to – were patient if tough negotiators, and explained to us that yes, we do need opening remarks, and three closing speeches. And it is important that we make sure that several institutions are represented, as well as respect the balance of gender and nationality of speakers. This is about legitimacy, and a conference with insufficient visibility of the institutions would have sent the wrong signal that we were just playing around while the grownups were doing the real policy work.

It did work, though. It worked almost too well. Turnout was huge, with some people coming in from all over Europe, but also from places like South Africa and the United Arab Emirates. The online buzz was just insane – I don’t think any Council of Europe event had ever become trending topic on Twitter before. The Twitter wall backchannel worked like a charm. There was some disagreement and a lot of frank talk, but all of it was respectful. Everybody I talked to – both from the community side and from the institutional side – absolutely loved at least some parts, and learned a lot from what he or she did not like so much. The community went home incredibly energized, and got down to doing the most advanced stuff I have yet seen done within a government project. Check out DemSoc leading a collaborative “letter to the funders” to start a negotiation with the funding agencies about rewriting funding rules for increased effectiveness and fairness (I do hope the European Commission reads that one); or Nadia trying on herself the “life without using money” way of living, guided by moneyless sensei Elf Pavlik. The Council of Europe behaved magnificently, showing care and appreciation for the young Europeans who had made the effort to get to Strasbourg. When the security staff agreed to let into the building Elf – who does not believe in states and refuses to use national ID – I knew the cultural battle had been won. I learned two things: that a fruitful, inspiring offline conversation can be had between institutions and a self-selected group of citizens; and that prior socializing online is critical to that conversation not disintegrating into squabbling about rules of engagement and what is meant by what.

As for the third bird, I have neither full information nor the authority to speak for the Council of Europe, or any other institution. I do know that Edgeryders, that started as a completely peripheral project – just a little money and a couple of lowly temps at the margins of the organization – has now gotten the attention of the most senior decision makers; and that a prototype is being designed for using Edgeryders-style engagement to elicit input into ministerial conferences on the most diverse subjects. This was before #LOTE: the day after we got two new proposals – one of which is to redeploy Edgeryders as a community of experts advising European cities on how to fight poverty. Funding, it seems, is not an issue. A door has been knocked down, and the Council of Europe is exploring what lies beyond it.

If I were more business smart, this would be where I tell you how hard it was, and how we heroically overcame massive obstacles. The gist of it would be that I am a very smart guy, and you might want to consider giving me a lot of money to work with you. But I am famously not business smart, and the truth is that doing all this has been embarassingly easy. Of course we had to work very hard, but even that is more a consequence of the grueling timeline (seven months from launch to #LOTE) than the actual content. It did not take new regulation. It did not require a change in leadership. It did not require innovation, other than some tweaking of Drupal and a few lines of Rails. It did not require flawless execution: we made plenty of mistakes, and I more than anyone. All it took was integrity, a respectful, inclusive stance, and careful deployment of existing Council of Europe administrative plumbing. I could do it again, and so could you.

This is cause for cautious optimism. All in all, I could not have asked for more to my year as a eurocrat, which has now come to an end.