Last week I was in London for the first jury meeting of the European Social Innovation Competition. We were guests of NESTA; its CEO Geoff Mulgan presided over it. Geoff is, in my humble opinion, one of the most interesting policy makers in Europe: even if we don’t always agree, when he speaks I pay attention. On this occasion, I was stricken by his insistence on the importance on measuring the impact of social innovation initiatives. Rigour and quantitative measurement, he finds, are essential to get rid of the hype and the faking that have deposited on the concept of social innovation over the last few years (his defining phrase: social innovation is “a bulls#!t attractor”).

I agree on the rigour part. On quantitative measurement I have doubts. Social innovators – the real-deal, disruptive ones – want deep change in society, so it does not make sense to assess what they do in terms of the very society they are trying to change, Take, for example, Bitcoin (Wikipedia) – an electronic for of cash designed so as to work in purely peer-to-peer fashion, with no central entity that can manipulate its value. It uses unbreakable cryptography to prevent people from spending their Bitcoins more than once, and it allows (unbreakably) anonymous transactions. I know personally people that advocate for it passionately: they are idealistic, generous folks, moved by the idea that bank-created “fiat money” is inherently flawed. There is only a small problem: unbreakable crypto and anonymous transactions are likely to lead to 100% safe fiscal evasion. Its detractors claim that Bitcoin has the potential to strike at the very heart of states, destroying their ability of imposing taxes. When you run this argument to Bitcoin supporters, many shrug it off: states, they say, are only good insofar as they solve problems for people. If their existence becomes a roadblock to problem solving, well – it might be time to look for something that works better.

Let me attempt to reformulate that. It’s not that these people are diehard revolutionaries. It is that, for the innovator, the status quo has zero value, less than zero in some cases. He or she assesses the impact of what s/he is trying to do in terms of the world that will contain the innovation at hand. Professional evaluators, working for government or private foundations, run their own assessment in terms of the world we have now, and ask the proposed innovation to improve it without changing it too much (they themselves are ruling class in the existing world, and it makes sense for them to treasure it). They are like Henry Ford’s clients that, in his own words, “would have asked for faster horses” because, simply, they could not possibly see clearly the car civilization without giving up important parts of their identity. Or like the Archbishop of Mainz, Gutenberg’s ultimate sponsor (through the “angel investor” Johann Fust), that supported the development of the printing press in the hope of producing an impact (cheap, fast indulgence certificates and bibles) that ended up, ex post, being insignificant; whereas its true impact (democratization of reading and writing, diffusion of heterodox religious material and ultimate victory for Luther’s reformation) would have made him recoil in horror. We consider the printing press a great step forward in the history of humanity, but this is because we are the children of the civilization that the printing press has spawned. We won that particular battle, so we get to write its history – if only because the losers have gone extinct.

Am I exaggerating? I don’t think so. Much of social innovation is out to redesign welfare. Welfare is a very important part of European identity: free and compulsory education, health care, provisions for the socially excluded. This stuff is, therefore, politically explosive. Try telling an Italian or a Swede “hey, looks like mass university is not working. Let’s scrap it and replace it with a system of Massive Open Online Courses”: what you’ll get, more often than not, is not a serene discussion, but an entrenched defense of the values allegedly underpinning the existing system (like “open and fair access to education for all”). Good luck arguing that the system is not particularly good at realizing those values, and that it makes sense to explore alternative routes: you are likely to be treated with suspicion and irritation (“There must be something fishy. Just in case, hands off our mass university”). So, the evaluator of social innovation projects finds herself in an uncomfortable position: if a project is low impact, there is no point in supporting it. But if it is high impact, supporting it could be very dangerous for the society in which the evaluation happens.

How to solve the dilemma? A technical solution could be to separate completely the function of promoting social innovation from that of evaluating it. In this scenario, you’d get a small scene of government agencies and private foundations tasked with maximizing the creative potential of social innovation, with a “take no prisoners” attitude and a complete disregard for existing societal equilibria; and a watchdog filtering out projects that threaten to be too costly in terms of foregone stability. But such a system is likely to be politically untenable – and then forecasting disruptive effects is at a minimum very hard, and could well be impossible even in theory because of positive feedback dynamics. While we wait for a better idea, I am afraid we will have to live with policies for social innovation that promote vanilla ideas and cater to the usual suspects, who stand guard to the existing order.

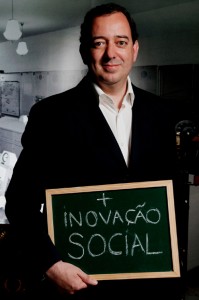

A year ago, people I know well and I have great respect of asked me to stand as a judge in something called the European Social Innovation Competition. It is a European Commission initiative; an attempt to honor the memory of the late Diogo Vasconcelos, a dedicated champion of social innovation in Eurospace. I accepted, and learned much in the process. I am honored to announce I was asked to serve as a judge for the second edition, and again I accepted.

A year ago, people I know well and I have great respect of asked me to stand as a judge in something called the European Social Innovation Competition. It is a European Commission initiative; an attempt to honor the memory of the late Diogo Vasconcelos, a dedicated champion of social innovation in Eurospace. I accepted, and learned much in the process. I am honored to announce I was asked to serve as a judge for the second edition, and again I accepted.