Elegant, influential theories have a way to rewire your brain. In my formative years, it was not uncommon to joke that Marxist intellectuals could and would explain absolutely anything in terms of Marxist dialectics. For all our joking, exactly the same thing happened to me, as I dug deep into neoclassical economic theory. I did have access to non-neoclassical theories, but in the end it is the math that makes the difference. Mathematics gives you a grip on the model: by manipulating it, you can stretch it, adapt it, critique it, own it in a way that you can’t really any other way. In the end, the mathematical tools you use to think about the world become a default way to parse empirical data: when your only tool is a hammer, you see every problem as a nail and all that.

The hammer of neoclassical economics is functions. Not just any old function: convex, continuous, differentiable ones – designer functions with smooth hypersurfaces. If everything is a function of this kind, everything (say, your country’s economy) must have a maximum, because (bounded) continuous, convex and differentiable functions have exactly one max. This means there is a perfect (“optimal”) state of the world. You find it by calculus. You can then hack your way around the system with taxes, subsidies and interest rates until you push the economy to that maximum. If you are a consumer, or a worker, you also will be looking at a function, representing your well-being. Again, you can find its max, fine-tuning savings and consumptions, work and leisure into your personal sweet spot. There’s no such thing as unemployed: hey, the function is not discrete! What you are seeing is people that choose to allocate zero hours to work, given the existing wage rate (I exaggerate, but not much).

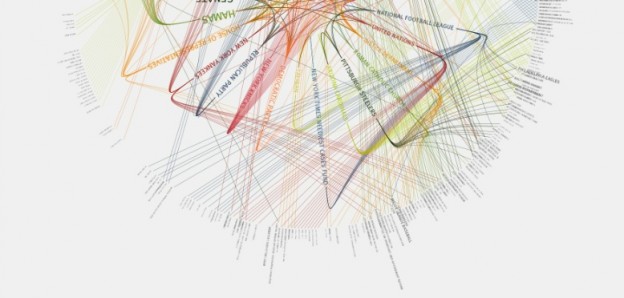

I spent the past five years learning how to use a new mathematical tool: networks. Going deep into the intuition of the math (as opposed to memorizing the equations) means, in the long run, a rewiring of your brain. What used to look like a nail suddenly makes much more sense as a screw. A good thing, since you are now the proud owner of a screwdriver! What I am seeing now as I consider public policies is this: I think of them as signals that the policy maker sends out. The interesting question is what carries the signal.

Traditional policy signals are broadcast: every agent in the economy receives the same message. Price signals (hence taxes and subsidies, too) are broadcast. So, in general, is regulation. Broadcast makes a lot of sense in an undifferentiated mean: if you want to reach a large number of recipients and they are all disconnected from each other, it’s a good technique. Just push that signal out in all directions, as loud as you can.

Once you really take networks on board, though, you start seeing them everywhere. And when you have all sorts of networks that could carry the signal for you, broadcast seems a blunt way to do things. Consider AIDS prevention policies. Broadcast policy sees that, as a category young people are more likely than old-timers to engage in unsafe sex, so it puts posters up in high schools. Since you can’t really be too graphic about it for political reasons, such posters tend to be quite bland, and immediately drowned by far stronger broadcasting signals that glorify sexual prowess and availability, those of commercial markets. Even if your average teen does become more careful, the epidemics still spreads through the very promiscuous few, who are unlikely to be impressed by a bland poster. All in all, near-zero impact is a good guess.

On the other hand, research has shown that networks of sexual partnerships are scale-free: a small number of individuals (not categories) have a very large number of sexual partners. These people are the main vector for the virus to spread. So here’s the networked version of AIDS prevention policy: go talk to the hubs. Dispatch researchers to identify them (it does not matter where you start, with scale-free networks it will take a small number of hops before you get to one); have one-on-one conversations with them. Spend time with them, they are important. Show them the data. Hire them, even. Should be cheap: it’s only a handful of people, who can have a disproportionate amount of impact on the epidemics by switching behavior. See the difference in approach?

In my talk at Policy Making 2.0 last week I tried to explore what it means, for policy makers, to think in terms of networks. I proposed that the gains from doing so are:

- impact: more bang for your taxpayer buck.

- reduced iatrogenics: policy becomes more surgical, so it causes less unintended damage.

- robustness to “too big to know”. Very simple network models exhibit sophisticated behavior. You can model several real-world phenomena without losing your grip on the intuition of the model, and therefore make more accountable decision.

- compassion. Networks owe their uncanny efficiency in carrying signals to large inequalities in the connectedness of nodes. Further, it is easy to build very simple models that produce inequalities even with identical nodes. This, at least for me, gets rid of the “underserving poor” rhetoric and fosters simpathy towards the smart and hard-working people out there that found themselves on the wrong side of system dynamics.

- measurability. Social interactions that happen online are now cheap to keep records of; you can use those record to build networks of interactions run quantitative analysis on them.

If you want to know more, you might find my (annotated) slides interesting. I am indebted, as ever, to the INSITE project and to all participants in Masters of Networks.