A couple of months ago, Simone Cortesi, deputy president of Wikimedia Italia and the primus inter mappers of Italy’s geohackers, noticed an oddity in the maps of the Revenue Agency’s property market dataset. How could they know about the walkways in his own garden? He realized he himself had uploaded those data, not into any government dataset but into the “wikipedia of maps”, OpenStreetMap. Since the maps did not credit OSM as the data source, the Revenue Agency was technically infringing on OSM’s intellectual property rights. OSM maps are free to use for all, but if you do use them you must respect the terms of the Open Database License protecting the data. If Simone’s allegations proved to be correct, this would be the largest ever copyright infringement against OpenStreetMap. And done by the tax authority of a G8 country, no less.

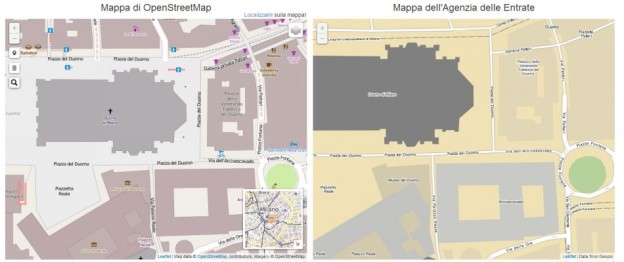

A group of Italian expert contributors to OSM coded a website exposing the problem and containing a tool for comparing the Revenue Agency’s “proprietary” maps with OpenStreetMap. Hundreds of eyeballs were put on the case, and sure enough, the data are the same, and the copyright infringement was there.

On July 8th 2014, after the Italian Twittersphere had put the word out, the Revenue Agency tweeted back that it had “demanded an explanation” from its technology provider, a company called Sogei. This is an in-house company, 100% owned by the Ministry of Treasury. Later in the day, Sogei complied with the terms of the OpenStreetMap license and issued a statement of apologies. With this, the generous Italian mappers declared themselves vindicated. Simone, bless him, rose to the occasion to demand the Agency opens up its own data, specifically those of the real estate registrar, as he and many of us in the Italian open data community have been advocating for years.

Over and above the embarassment, there is a deeper lesson to learn here. Sogei is a monopolist: the Revenue Agency had no choice but to get its tech from them. Sogei, in turn, ostensibly acquired their geodata from a company called Navteq, (source, in Italian), owned by Nokia (wikipedia), that appears since to have changed its name into Here.

So what happened, really? Did Navteq repackage free and open data and sell them as proprietary to Sogei, who resold them back to the Italian state? How much money was spent on this procurement process? Was there financial damage to the public purse, and was it intentional (hence an offence)? How much money could we have saved, and keep saving, if smart communities like the OSM, open source and open data communities were involved in public procurement?