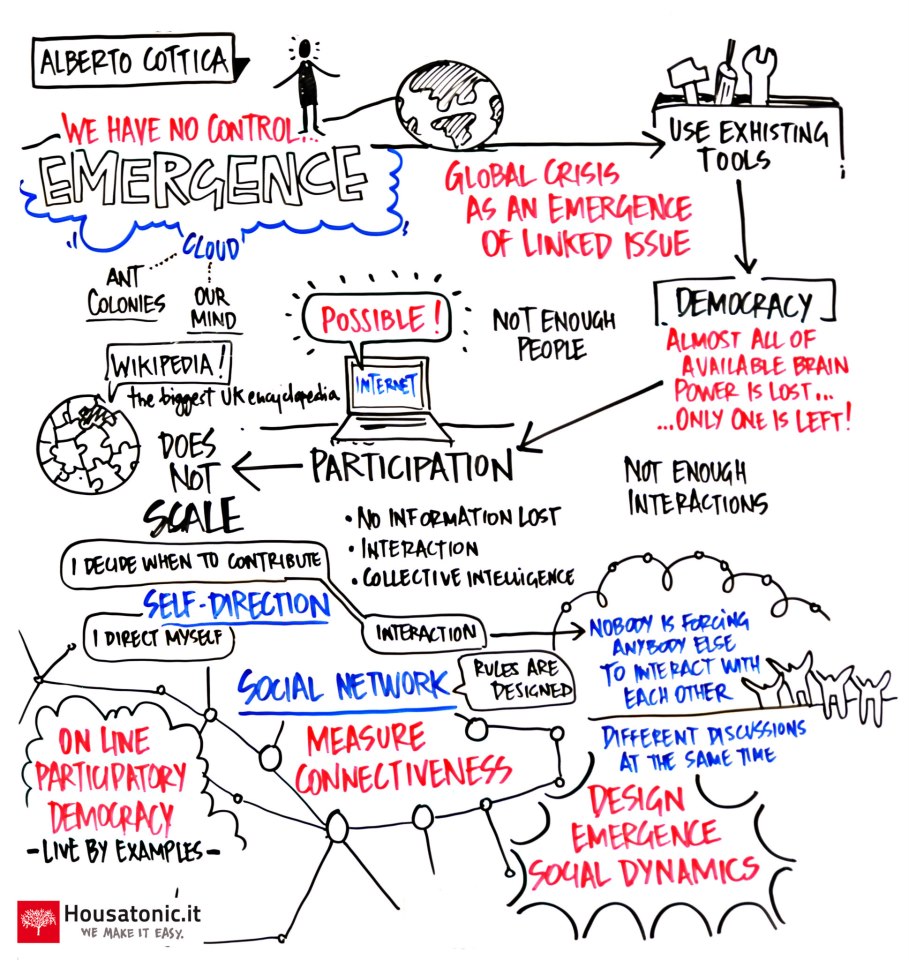

Try proposing to use the Internet to extend the space for democratic dialog: everyone will agree with you. Extending the space of democratic dialog can’t be wrong. Or can it? Even as they agree in principle, I’ll bet you that someone will be frowning: yeah, sure, but… not everybody is comfortable around computers. What are we going to do about the elderly? The less educated? The disabled? All around, others will be nodding sagely. We need to be careful, to proceed with caution. If the spaces for electronic democracy are too broad, we risk giving extra political clout to the connected élites, and to marginalize further the marginal.

I understand where these doubts are coming from. And yet, how come they have not been cleared away? Competent technicians and visionary political leaders have been experimenting for years with computer network as a space for political discourse and public governance. What have we learned in those years?

The first democratic institution to open a space for citizen participation based on a computer network is, to the best of my knowledge, the city of Santa Monica, California. Its Public Electronic Network (PEN) launches in February 1989. Not the Internet: PEN was a local network. At its core is a Hewlett-Packard minicomputer. Citizens connect via modem (if they own one – not very common in 1989) or using terminals located in the city’s library.

In 1993 the city presents an evaluation report on PEN’s first four years. The main points are:

- More than 80% of system usage is accounted for by user-to-user interaction, via email (20%) and above all on the public forum (60%+).

- Most of the 85,000 residents don’t use PEN, that has 3,000 registered users. Most users don’t take part in the discussion: only 5-600 log into PEN every month, and the hardcore users, who wrote the bulk of the contributions, are only 50-150.

- PEN users are on average richer, more educated and more interested in politics than Santa Monica average residents.

- some homeless resident take part in the online discussion in an active an visible fashion. This participation gives PEN it’s main political success, so it’s worth telling the whole story.

Since the start, the homeless PENners manage to get across their main problem. If you live on the street, it’s difficult to look presentable; and if you don’t, no one will give you even the lowliest job, so you can’t afford a place to live. In August a PEN Action Group kicks off, led by a university professor. Homed and homeless residents, together, design a new service they call SHWASHLOCK: public showers open since early morning to wash before taking on the new day; washing machines to wash clothes; and lockers to guard the homeless’ possessions. No public agency or NGO in town supplies the service, despite the Santa Monica Chamber of Commerce’s declaration that homelessness is “the number one problem in town”.

The Action group raises funds; convince a city agency to administer a system of laundry vouchers; approaches a locker manufacturer, that agreed to donate some to the city. In July 1990, rising to the opportunity, the city hall launches SHWASHLOCK. Meanwhile, the city’s help center for the homeless is equipped with a PEN terminal, to facilitate access to the service.

The 1993 report is signed by Ken Phillips, the City Hall’s director of information; Joseph Schmitz, university researcher and co-designer of PEN; his colleague Everett Rogers; and Donald Paschal, a homeless resident. Paschal writes: “PEN is a great equalizer. No one on PEN knew that I was homeless until I told them. After I told them, I was still treated like a human being… the most remarkable thing about the PEN community is that a City Council member and a pauper can coexist, albeit not always in perfect harmony, but on an equal basis.” (Source: Wired).

What’s going on here? How to reconcile the high income and university education of most PEN users with the feeling of fairness and equality reported by Paschal and other homeless residents?

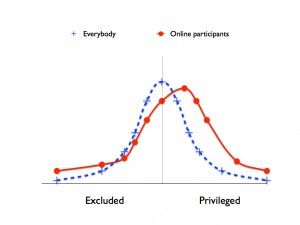

There is a simple explanation: the digital divide does not coincide with the traditional social exclusion rift. Consider an old guard politician: degree in law or medicine, reads five newspapers a day, local network of voters based on physical presence (“manning the post”). Not much technology: he was probably given an iPhone, and uses it to actually make calls. This person is fully included in his society, even influential, but is digitally excluded. Now consider, at the opposite end of the spectrum, a twentysomething in precarious employment, with a nontechnical degree from a second-tier university, living hand-to-mouth with little or no hope of long-term employment, hyperactive on several social media. This person is digitally included, but risks overall exclusion. Opening an online space for citizen participation to decision making increases the political clout of the young underemployed and reduces that of the old guard local heavyweight. Digital inequality interferes with pre-digital inequality. The net effect is a reduction of overall inequality. We saw this clearly in Egderyders, that aggregated people generally good around technology… but some of whom are definitely poor. I know of at least four of them who practice dumpster diving for discarded perfectly good food. Three of them are computer programmers. Are they underdogs or members of the élite?

The other cause for the reduced visibility of the median elector on the Net is the high commitment required to be a protagonist. You are not talking about casting vote every few years: people here need to discuss, stay on top of the main threads, make convincing case, research. Most people are simply not interested enough; those who are tend to be more educated than average (and also richer, since income end education correlate well).

These two effects combine to produce the environment typical of online platforms for civic participation – with an overrepresentation of the intellectual élite, but also of the marginal groups. In my experience the interaction between socially diverse people is exactly what makes online participation so interesting. There’s a reason for that: diversity produces innovation. SHWASHLOCK was so refreshingly no-nonsense, and it worked so well, because it incorporated both the first-hand knowledge that the homeless have of their situation and the access to resources and political capital of wealthier residents. These conditions are difficult to reproduce in traditional political arenas, which tend to treat the excluded as a problem category rather than potential problem solvers – with the results that they get discouraged and withdraw, or take on a passive stance.

So, do Internet-based political participation arenas increase equality among citizens? It depends. If we look at equality as diversity, extending access to political influence to a broader range of citizen categories, the answer is yes. It is no chance that the first-ever public policy designed online by citizens zeroed in on improving the life of the most vulnerable among them. If we look at equality as statistical representativeness, then the answer is no. We have known this since 1993 – that’s twenty years ago. The discussion is over, and it is unacceptable to use it to block a broader access to public decision to citizens other than the usual suspects of traditional policy.

Some have proposed to tweak online participation to make it more representative of the electorate. My experience suggests this would be a very. Bad. Mistake. Far better to listen to the median elector’s voice through traditional participation channels, and use the Internet to make the most of the innovative solutions and challenges that might come – rather, that have always come – from the underprivileged: the homeless, the poor, the disabled, the young, the lifestyle hackers, the sexual, ethnic, religious minorities. Their voices are precious because, let’s all remember, diversity is fertile ground for innovation, and because we have so few spaces in which we can really talk to each other from an equal footing. The Internet enables us to build such spaces: let’s not waste the opportunity.