Since about a year I have been running somewhat regularly. I started just to have an alternative to the gym when I am on the road, but my motivation have gotten deeper since. Running opens a door on a new and interesting path, not just for me but for all of us.

Here’s the thing: running generates data. A lot of data. Data about us. And we consume them, with ever-growing appetite.

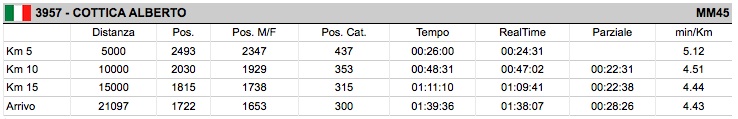

Consider, for example, the Stramilano half marathon, which I run just Sunday. Its over five thousand participants were possibly the most technology-enhanced large group I have ever been part of. Each runner bears a number tag which incorporates a transponder; combined with the sensors scattered along the route and a precise chronometer, this enables very precise tracking of the bearers’ performance. Here is mine:

There is a lot of information in this table. Not just my final absolute- and category placement; not just my official (from start to finish) and real (from the moment when I crossed the starting line to when I crossed the finishing one) time; but all of these, plus cumulated average speed, at four different checkpoints 5, 10, 15 from start and at finish. As you can see, I had a few problems in the early stages, with a low average speed of 5’12″/km (I got stuck behind a phalanx of slower runners). Then it got better: my average speed increased to 4’30” for the following ten kilometers, then decreased slightly again for the last six. At the start I had probably some 4,000 runners in front of me; after 5 kilometers I still had 2,500; in the last sixteen kilometers I overtook almost 800 more. My worst mistake was not try to get further towards the front of the starting grid; this cost me something like two minutes of rel time and three on official time.

But this is just half the story. Practically every athlete in there was equipped with some form of data generation and monitoring: GPS units in their pockets, accelerometers inside their shoes, heart rate monitors on their chests, chronographs on their wrists. Data were processed locally and fed back to the runners in real time; after the race they were downloaded on massive cloud computing systems and processed again to keep track of progress and programme future training. I, for one know full well that I have run 609,17 km since late July 2010. It took me 51 hours, 3 minutes and 3 seconds, at an average speed of 5’03″/km and burning 39.305 calories. I know absolutely everything.

This knowledge gives me control. The data, once processed and interpreted, make us faster. Athletes with a little experience use them to decide on competition strategies. If you run in large groups, you’ll hear beeps and alert going off at every turn, and it is not uncommon to hear remarks like “we are ten seconds late on our flight plan”. The Stramilano crowd was running amidst a cloud of computation.

Running is just an example of a general trend towards an ever-increasing computational density of our lives. We monitor, record and quantify our trips, our social and professional networks. More and more often we do the same for our physical existence, tracking metrics like weight, glucose levels, body fat. We sequence our DNA. For each of these metrics, be they social or physical, we have online services that allow us to share them with others and turn them into conversation topics (and we do it, not overly concerned with privacy). Americans talk of “quantified self”: it is a rapidly growing movement, because data allow us to explore how our bodies react to different stimuli, and adjust our behaviour accordingly. If I discover that a certain training routine improves my performance, or a certain diet lowers my body fat, I can use them to meet my goals in terms of running, or just looking good. If I quantify my body, it becomes easier to hack it.

The word “hacking” in this context is exactly right. Like the original hackers, body hackers are outsiders to the system, so they can afford to be radical. Like Tim Ferriss says: “I am neither a doctor, nor a Ph.D. I don’t have a publish-or-perish career. I can test hypotheses using the kind of self-experimentation mainstream practioners can’t condone. By challenging basic assumptions, it’s possible to stumble upon simple and unusual solutions to long-standing problems”. Spoken like a true hacker. In other words, I teach myself some knowledge, then I use a low-access technology to tinker around. When enough people do that, open innovation happens.

The Stramilano half marathon was a wake-up call: self quantification is becoming a mass phenomen. Expect a wave of open innovation, and a new generation of hackers. But this time it will be our own bodies acting as both labs — and prototypes.