I took part in a super-interesting session at the European Week of Regions and Cities. We debated citizen engagement in a refreshingly hype-free way – no one even mentioned any magic app or technology, it must be a first in the 21st century. I took home a number of points from my fellow panelists, that I detailed elsewhere. This post presents in written form my own opening remarks, and the question I asked the panel.

Citizens’ participation to the definition, implementation, and monitoring of public policies is perhaps my central interest. I have a background in regional development, and that led me to look into citizen engagement with a lot of attention. If you have done any regdev at all, you will know how important it is for the local people to support what you are doing. Getting anything done in the presence of substantial opposition is impossible, of course: but many projects lose steam and ultimately fail just because there is not enough positive will to make them happen. In my country of origin, Italy, there is a landmark study by Luigi Bobbio, who followed 100 local development initiatives over five years; by the end of the study, only 5 had been completed, with all the others being mired in procedural complexity, NIMBY fights, polemics.

So, in the early 2000s, I started to think we could use the Internet, that at the time was becoming a mass commodity, to engage citizens on our work. Over the following years, I built up substantial experience, mostly while working for the Italian ministry of economic development. In 2010 I felt that experience was mature enough to become a book on “government by wiki” and collective intelligence.

In the 2010s, I left government and became more of a researcher, but I kept following this idea, within the context of my current home, Edgeryders. Over the years, we have become quite good at engaging citizens on large online dialogues, which we think of as networks of social interaction carrying content, and performing sophisticated analysis on it.

It’s not easy, but it can be done. And when people ask us “How do you get people to engage?” There are always two answers. The first: have a fair social contract underpinning the participation. Someone asks you “what do I get for the time I put into participating?”, you need to have an answer. The second: ask interesting, relevant, mobilizing questions. And this brings me back to regional policies.

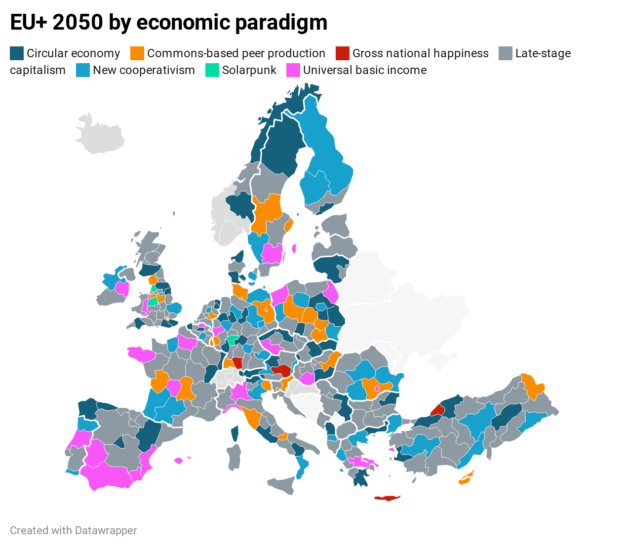

The principle driving regional policies in Europe is called convergence. It is inspired by maps like this one – that you have seen it million times in one version or another. The idea is that what is different should be made the same. Moreover, there is a clear ranking: Thessaly should become like Bavaria, not vice versa.

Convergence is there for a reason: it reduces the scope for competition between low- and high-labor costs regions, and this way makes transitioning to the Single Market less traumatic. However, I think it is not a mobilizing issue for citizens. For two reasons.

The first one: the model underpinning convergence needs to be changed anyway. If we take seriously a transition to low carbon, the idea that more growth is better needs an overhaul. At a minimum we need to refine our definition of what should be growing.

And this brings me to the second reason: Europe is a mosaic of cultures, traditions, lifestyles, and people do not like theirs to be considered inferior to another along some arbitrary scale. It’s a bit like looking at a cat and saying it’s a lousy dog: it is not false, but it kind of misses the point of that a cat is, and what it brings to the table. And indeed, convergence does not work very well. Many peripheral regions have been struggling for decades, only to find themselves the eternal laggards. This breeds not engagement, but cynicism and resentment towards the European project.

On top of that, despite very substantial effort being invested into it, it is not clear that the model is working that well. The EU and its member states invest roughly 100 billion EUR per year on cohesion policies. Despite this, the Commission’s own analysts report that convergence slowed down or stalled after 1995. I have my own thoughts about how and why this happens, but let’s leave them for another day.

So, what if used citizen engagement to ask a very different question?

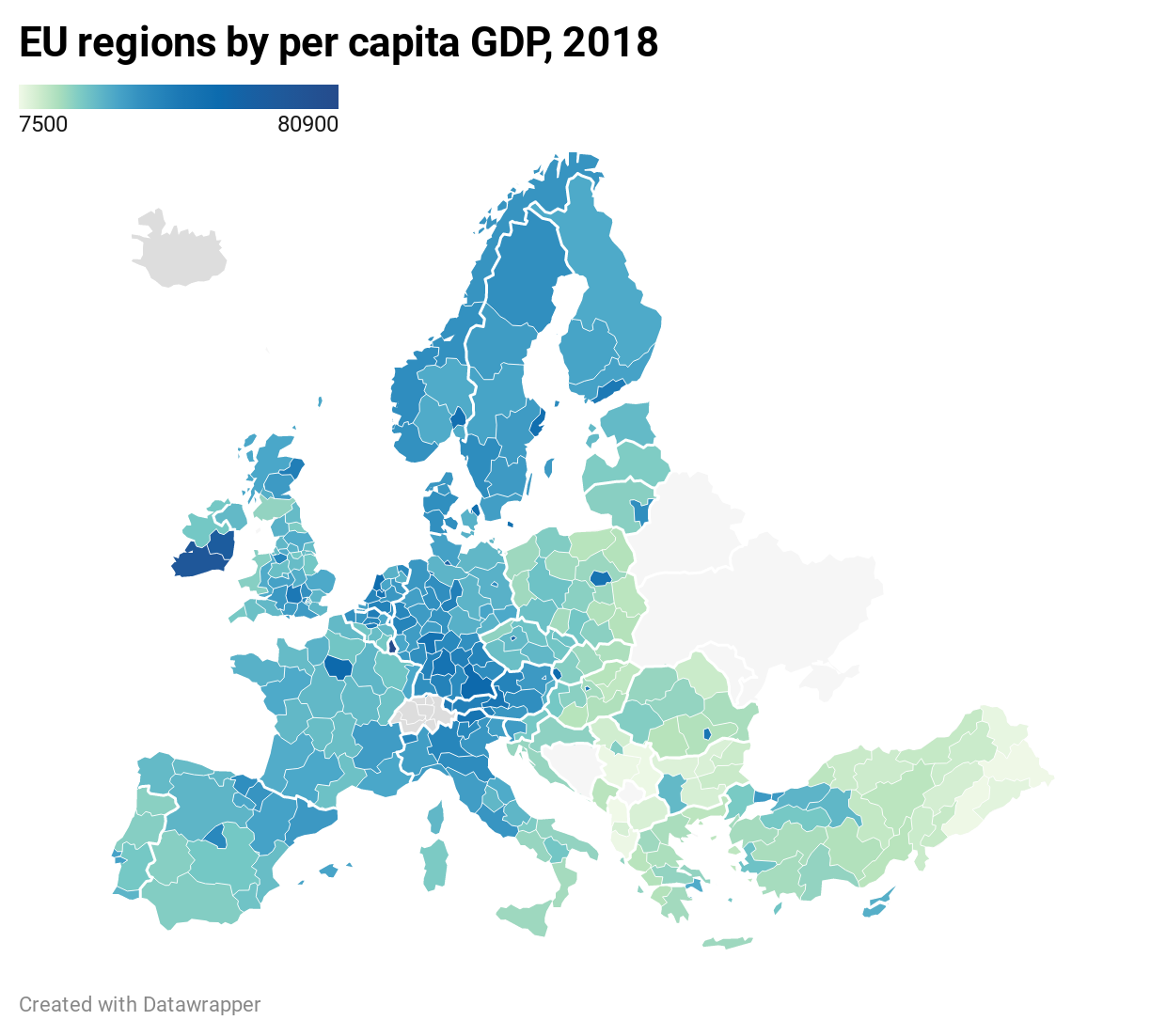

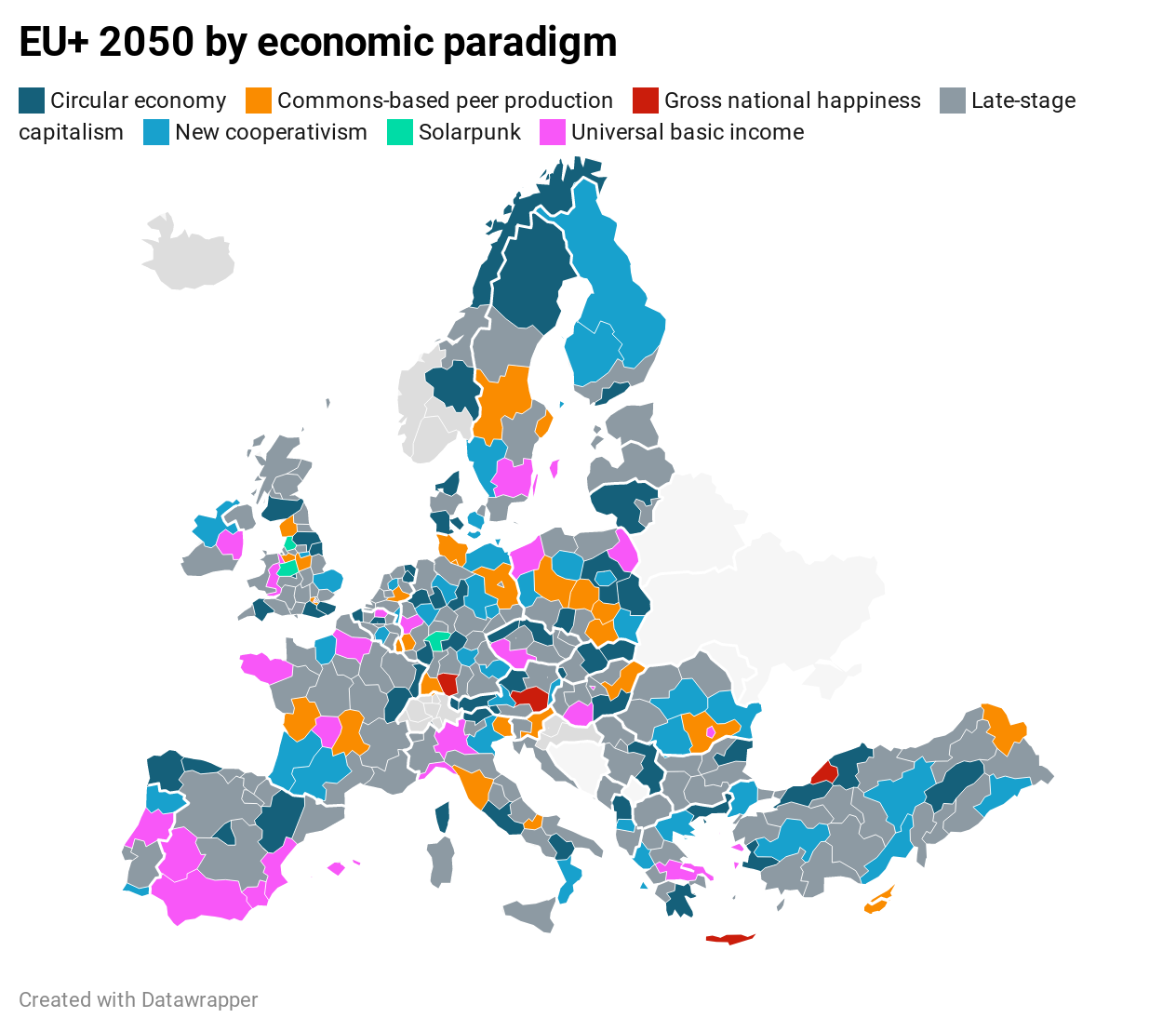

What if we asked European regions, especially at the periphery, not to try to “catch up” with Bavaria, but rather to lead in experimenting with different economic systems? Maybe Thessaly does not want to be like Bavaria after all. Maybe it wants to be like Bhutan, promote harmony and “gross national happiness”. Maybe Pomerania wants to try a high-efficiency, low-GDP economy based on public goods. Maybe Sicily wants to try being a solarpunk utopia of mostly self-sustaining communities. As these regions move up the learning curve, their learning benefits us all – we can copy from them. the former laggards, what they have found to work. They would also, presumably, learn from each other, and those running on the same economic operating systems would form inter-regional alliances. The map of EU regions would no longer be shades of one color, but rather a mosaic of different colors, like this:

If you are a science fiction reader, this will look familiar. It’s how I imagine a map of Phyles in Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age, or of Hives in Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota novel, or again of Centenals in Malka Older’s eponymous cycle. This is no coincidence: these authors all explore the real-world idea that nation states are no longer fit for purpose. The EU itself has no small part in making this idea attractive to speculative minds.

It might sound radical, but remember it’s how China did it. In 1980, president Deng drew a curve on the map around Shenzen and said “Let’s make a capitalist economy, but only in this special economic zone”. When that proved to work, arrangements in Shenzen were debugged and scaled to the country, with the results you are seeing today.

My hunch is that a radical, honest approach to regional policies would lead to much more, and better, citizen engagement, ultimately boosting the moonshot of the green transition. And we need that boost, as time is running out. If you, like me, are up for exploring this notion, get in touch. It would be really nice to have an experimental programme where regions would be encouraged to explore alternatives to our current economic paradigm.