Author’s note: this is not an academic essay. It’s more of a long, wonkish blog post, that borrows some characteristics from academic essays. If you think it should be published elsewhere, get in touch. If you want an Italian translation, ask for one.

Abstract (TL;dr)

Public policies in the past few decades have failed on many levels. While many economists have been critic of such policies, economics as a discipline was not able to deliver a better paradigm. I examine some recent work by five authors: David Colander, Roland Kupers, Mariana Mazzucato, Eric von Hippel and Ricardo Hausmann. I argue that, taken together, their contributions herald a completely new way to think about policy making. This new paradigm is the brainchild of complex systems science. It implies that policy makers should have a new skillset, new tools, new indicators and even new goals.

1. How economics failed us

Economics has made a bad name for itself.

- In the 1980s, the Chicago School rose to prominence with its recipe of inflation control and fiscal conservatism. It inspired the controversial reforms of the Reagan-Thatcher era, and marked the beginning of the end for the European welfare state.

- In the 1990s, the Washington Consensus ideology pushed upon the whole world a policy toolbox of fiscal discipline, privatisation of public services and liberalisation of capital movements. These policies were responsible for the mismanagement of the financial crises of those years.

- Then came 2008 with its Great Financial Crisis. We were plunged into a strange world. In the West, negative interest rates, quantitative easing, skyrocketing inequalities, “too big to fail”. Globally, a reduction in the number of the poorest, and the rise of China over Southern Asia and Africa.

All through this, economists have put up quite a fight. The top names in the profession have denounced the inconsistencies of the dominant doctrine. Joseph Stiglitz exposed the International Monetary Fund’s mismanagement of the crises of the 1990s. Paul Krugman explained why fiscal discipline was the wrong thing to do in the wake of 2008. The list could go on and on.

But policy makers remained unimpressed. Yes, mistakes were made. Yes, some excesses needed correcting. But in the end, no other paradigm was available. Dissenting economists had strong critiques, but weak counterproposals. In the 1930s, Keynes proposed a new paradigm. It was elegant. It was operational. It offered a new way out, and policy makers embraced it. But now? No new paradigm is in sight. Standard economics is the only game in town.

Except it is not. Over the last few years, four economists and one physicist have made groundbreaking contributions. I propose that, taken together, they form the seed of a new way to think about economic policy. In what follows, I list their main contributions. I then discuss the implications of taking them together, rather than one at a time.

2. David Colander and Roland Kupers: complex systems theory as a frame

Scholars of complex adaptive systems see the world through the lens of a process called emergence. The idea is this: simple rules of interactions between agents give rise to surprising system-level properties. These properties of the system cannot be deduced by studying its components. For example, water is a liquid at room temperature. It sloshes and shimmers and does many interesting things. A single water molecule is not a liquid: liquid-ness is not in the molecules themselves. It emerges from the interaction across billions of identical molecules.

Porting this way of thinking to policy making is difficult. The starting point is this: society and its economy are no longer seen as machines. No longer can the government push the right buttons to get them to social optima. The world of traditional economics goes down in flames. So what can the government do? There is a fundamental clash: policy is about agency, intentionality, top-down process. Emergence is the opposite of that: structure happens without designers or architects. A complex system with agency in it (for example an economy with a government) is driven by two fundamental forces, emergence and agency itself.

To navigate the dilemma, Colander and Kupers propose a government that “picks its fights”. It strives to spot emergent trends that go in the direction that it wants, then moves to reinforce them. One example they give is the trend towards physical fitness and healthy living. A complexity-oriented government would move aggressively to support it, and so save taxpayer money on health care.

This has profound implications. The main one is that the government needs a new set of core skills. Among them:

- It needs to be great at scanning the horizon for useful social trends. This is by no means easy: we now see fitness as a trend, but in the early 80s there was no such thing. People would see their cousins taking up aerobics or weightlifting, and shrug them off as weirdos. It took serious analytical skills to recognise it for what it was.

- It needs to be strong and nimble, and use strength and nimbleness as a source of moral authority. When it moves to support something, private business and the public need to know that this something is here to stay, and that support will not waver.

- It needs to choose, and take responsibility for its choices. No more handwaving about “leadership of the private sector”. No more bullshit about impartiality. We stand for nuclear, or against it. We stand for genetic engineering, or not. And when we choose, we stay with our choice for as long as we need to, not until the next election.

3. Mariana Mazzucato and Eric von Hippel: rethinking innovation

When we think about innovation, we think about Schumpeter’s creative destruction. Stories of innovation are stories of brave, disruptive entrepreneurs who “stay foolish” as they follow their own vision. Mazzucato shows that these stories are mostly false. Aggressive state intervention was the decisive driver in kickstarting today’s hi-tech industries: IT, biotech, nanotech, green energy. Moreover, at least for IT, the (American) state’s motives were not even economic, but related to national security. The protagonist was the Pentagon, not Treasury. In the case of China, a similar dynamics is now playing out with green energy. The main policy driver is preventing climate change and pollution. A world-leading green energy sector emerges as a result of that policy.

In these stories, private business and venture capitalists consistently show risk aversion and short-termism. They do “me too” innovation and polish. An entire chapter of Mazzucato’s book is dedicated to Apple’s iOS devices. It turns out that all the key technologies putting the “smart” in smartphones are taxpayer-funded. It’s worth listing them here: microprocessors, DRAM, micro hard drives, LCD displays, LI-ion batteries, DSP signal processing, the Internet, HTTP, HTML, cellular technology, GPS, multi-touch screens, and SIRI. Apple added technology integration and design, but did none of the innovation heavy lifting. Mazzucato concludes that the State, not private firms, is the real disruptive agent:

In sum, “finding what you love” and doing it while also being “foolish” is much easier in a country in which the State plays the pivotal serious role of taking on the development of high-risk technologies, making the early, large and high-risk investments, and then sustaining them until such time that the later-stage private actors can appear to “play around and have fun”.

von Hippel starts at the opposite end: what he calls “free innovation”. This is innovation developed and given away by consumers (patients, tinkerers etc.). This is by no means marginal. It is a major economic phenomenon. It involves tens of millions of individuals in just six countries surveyed (Canada, Finland, Japan, South Korea, UK, US). Estimated free innovation R&D expenditure has been estimated for three countries, and found to be on the same scale of corporate R&D. These estimates are likely to be conservative: free innovation in services, for example, has been left out of them.

Moreover, free innovation tends to lead producer innovation. There can not be a market for something that does not exist yet. For-profit corporations only service markets, so they focus on incremental innovations. But people don’t care about markets: they innovate for themselves and their friends. Some of their innovations go viral and create markets that, later, producers supply with innovations of their own. This happens across the board: 3D printers, scientific instruments, health care, whitewater kayaking.

From opposite angles, Mazzucato and von Hippel see the same reality. Business is not the sole agent of innovation. It probably is not even the main one. What’s more, the innovation that it does do is uninspiring: low-risk integration of ideas developed elsewhere. Glass beads and trinkets. Their work dispels for good Silicon Valley’s claim that “we take high risks, we deserve our high profits”. The truth is this: all the main risks are underwritten by ordinary people. As taxpayers, they underwrite risky government-funded research projects. As free innovators, they directly develop technologies and create markets for them. What’s left for the companies is to take the goodies, make a grab for the money and (all too often) siphon profits to some tax haven. Mazzucato calls this configuration “parasitic”. She is right: it socializes the risks of innovation, but privatizes its rewards.

They also show that money is not the motivator of the best innovation. States innovate to further a collective vision (“go to Mars” or “stop global warming”). People innovate to help themselves and loved ones (“I built a wearable monitor the glucose level of my diabetic child, so she can sleep over at friends”), or just for fun.

4. Ricardo Hausmann: economic well-being as a set of capabilities

Hausmann and collaborators have succeeded in redefining what it means for an economy to be healthy. This is no small achievement. GDP is broken: bad things like illnesses, car accidents and pollution all make it go up, not down. Economists have been muttering and complaining for as long as I can remember, but GDP has stayed. In 2008, The French government even tried assembling a super-high-level commission. Headed by Amartya Sen, Joseph Stiglitz and Jean-Paul Fitoussi, it could count on the cream of the crop in the economics profession, including five Nobel laureates (Arrow, Heckman, Kahneman, Sen, Stiglitz). The results were disappointing. There was handwaving about “multidimensionality of well-being” and “pragmatic approach towards measuring sustainability”. Everybody went right on using GDP.

Hausmann takes a different path. He thinks that a healthy economy is one that can make many things. A country that can make machine tools and aircraft and nanotubes is healthier than one that can only grow bananas, or pump oil. This has got nothing to do with how much money people in the country are making. It’s got everything to do with how resilient economies are. Economies that can make a great many things can engineer their way out of many shocks. For example, if you have good solar tech you are more robust to fossil fuel shortages.

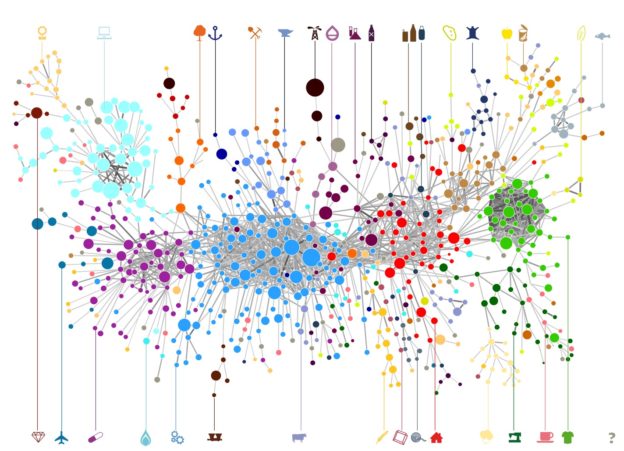

Hausmann and collaborator Cesar Hidalgo invented product space, which makes this concept operational. The main idea is that what countries make reveal what they know. They start by international trade data, and build a graph of countries and products. If a country exports one product, the two are connected in the graph. Next, they apply graph theory to derive measures of economic diversity. To a first approximation, diversity is simply the number of products a country exports. More sophisticated measures include second- and third-order effects. For example, products that are exported by few countries (like medical equipment) carry higher diversity than products that are exported by many countries (like wooden logs).

Product space analysis gives us a single number that summarizes the economic diversity of an economy in a given year. You can then compare different economies, just like you do with GDP per capita. You can also check back every year or two to see how much diversity is growing, just as with GDP. Except that diversity-as-health makes sense, whereas transactions-as-health do not. Its underlying formal principles are also more intuitive: product space descends from network math, GDP from double entry accounting. Most people with no formal training in either find networks simple, and accounting intricate.

5. Coda: policy as long-term risk management in a complex world

Where does that leave economic policy? Each of the contributions I listed has strong, direct, operational policy implications. But I propose that, taken together, they form a whole greater than the sum of its parts. They outline a new approach to economic life, and to policy enacted upon it. This new framework stems from the 35 years long love-hate affair between complex systems science and economics. What follows is a rough, tentative approach to summarize it.

- We don’t have control. The world is big, complex and in constant flux. We are nowhere near to understanding it in full, let alone dominate it. The idea of computing and achieving social optima is nonsense.

- Focus on the “how” questions. The above looks like harmless common sense, but is has profound consequences. The main one is this: we can no longer assume markets will find the social optimum by themselves. This is not because of market failures: general equilibrium theory is discarded altogether. Markets become mere tools to allocate specific resources. This, in turn, means that economics gives up on answering the “what” question (as in “what should we do?”). It is up to humans find out, in their own messy way, what a desirable outcome looks like. Economics goes back to focusing on the “how” question (as in “how shall we get there?”), consistently with its origins as a spinoff of moral philosophy. I am grateful to Fabrizio Barca for this observation.

- Policy is about society-wide risk management. The policy maker’s job is to manage risk. This involves scanning the horizon for trouble (frequent) and opportunities (rare). Risk is a constant in the journey of human societies: all we can do is manage it, weighing potential gains against potential losses. Uncertainty will always be high. Companies and households, of course, do the same. The difference is that policy makers can and should do this for society as a whole, making the hard choices that individual actors won’t do, and allocating risks and rewards across society. The allocation has to be long-term sustainable. Mazzucato, for example, points out that US innovation policy is not sustainable, because its risks are borne by taxpayers and its rewards are reaped by shareholders and executives. Over the long run, this will result in political backlashes and instability, which in turn will kill the State’s ability to invest.

- It’s all about the skills. Upskilling your economy is the best risk management tool. The more things you can make, the greater and more diverse shocks you can withstand. Hausmann has a great quote: “don’t add value to your raw materials, add capabilities to your capabilities”.

- Corporations are just a tool, and not always the most effective one. Mainstream economics fetishizes companies and profit for many reasons, theoretical and otherwise. But when you think in terms of risk management, you start to see things in a new light. Suppose you, as a policy maker, believe climate change could badly hurt our societies. Suppose you plot a transition to a deep green, low-emission economy. People from business come to you and protest “this is going to hurt out bottom line, we won’t cooperate”. If you believe GDP embodies human happiness and it is your duty to maximise it, you will listen carefully. If you a risk manager, you are more likely to brush them off. Your duty is not towards shareholder value, but towards deflecting large risks. If companies won’t collaborate in building the new infrastrure you want, you will work with different tools (public sector agencies, for example).

- Arbitrariness is inevitable. Risk management should be evidence-based. But any risk manager will tell you that, at the end of the day, you will have to make calls. Many of these will be in terms of uncertain gains versus certain costs. Should we bail out this bank? It might save us from contagion and systemic crisis in the future, but it sure will cost us taxpayer money now. Are Arctic glaciers worth the demise of the oil industry? You get the idea. This is the core of the trade of policy making. There is no such thing as sitting back and letting social optima emerge from market equilibria. Policy makers just have to make hard calls. Which means they will sometimes (often, even) fail. There is no way to avoid this. Colander and Kuper insist on the government needing “moral strength” to do its job.

This is a high-level description. But the theory of policy making in a complexity framework is mature enough to have produced tools, practices, indicators. And boy, do they look different from what we are used to. I already mentioned product space. Both Mazzucato and (especially) von Hippel have built solid empirical methodologies to inform innovation policy. Hausmann even wrote a convincing critique of randomized control trials, the gold standard of empirical research in economics. His tool-of-choice is “crawling the design space” of policies in a decentralized fashion. Money quote:

As opposed to the two or three designs that get tested slowly by RCTs (like putting tablets or flipcharts in schools), most social interventions have millions of design possibilities and outcomes depend on complex combinations between them. This leads to what the complexity scientist Stuart Kauffman calls a “rugged fitness landscape.”

That’s what evolution does, and this is no coincidence. Hausmann is a complexity scientist himself, and thinks more like a biologist than like a neoclassical economist. The Kauffman quoted is a theoretical biologist, not an economist. Everything changes. It’s a whole new paradigm.

Conclusion. A new paradigm for policy making is warming up in the background. A lot of the foundational work has been laid out. Much work remains, but that’s no excuse not to start deploying this way of thinking right now. All we are missing is a few forward thinking national or regional governments willing to be early adopters. I think I will see such adoption in my lifetime. This is good news for everyone, but great for us economists. After decades of deadlock and frustration, it appears we, once again, have a large contribution to make. I want to end with my all-time favourite public policy quote. It is attributed to the very first complexity economist, Brian Arthur.

If you think that you are a steam boat and you can go up the river, you are kidding yourself. Actually, you are the captain of a paper boat drifting down the river. If you try to resist, you are not going to get anywhere. on the other hand, if you quietly observe the flow, realising you are part of it […], then every so often you can stick an oar into the river and punt yourself from one eddy to another.

Amen.

Reading list

- Colander, David, and Roland Kupers. Complexity and the art of public policy: Solving society’s problems from the bottom up. Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Hausmann, Ricardo, et al. The atlas of economic complexity: Mapping paths to prosperity. MIT Press, 2014.

- Mazzucato, Mariana. The entrepreneurial state: Debunking public vs. private sector myths. Anthem Press, 2015.

- von Hippel, Eric. Free Innovation. MIT Press, 2016.