Much has been written on the campaign that led Giuliano Pisapia to being elected mayor of Milan. Analysis on the role of social media, Twitter in particular with the #morattiquotes and #sucate is begining to circulate. There is no doubt that the Pisapia-Boeri campaign was very collaborative (more than forty thousand users tweeted with the #morattiquotes hashtag); and that Pisapia himself played ball, taking a step back and letting his supporters do the heavy lifting of voicing for him, in the way and on the media they liked. I am not qualified to comment on how this campaign will change political communication in italy.

I do want to highlight that, as the campaign drew to a close and victory was declared, something unexpected happens: the loose collaboration between Pisapia the candidate and his supporters did not end with it. The first message that Pisapia the mayor delivered to the city was “Don’t leave me alone”, and his words rang sincere; a few hours later, to a journalist asking him how he would deal with the inevitable pressure of interest groups he serenely replied “There are hundreds of thousands of Milanese out there that are not going to let me sell out” (video, at 8′ 50″). Message received, loud and clear: Pisapia believes in the wisdom of “his” crowd. In this sense, he is a real wiki leader.

As the mayor seems to want to create, within his administration, some space that citizens can help fill with content, like a Wikipedia page, his supporters are giving signs that they want to play along. On Friday June 3rd, just four days after the election, a new hashtag spread over Italian-language Twitter, #pisapiasentilamia (Pisapia, hear my voice). The light-hearted tone recalls the campaign, but the content is serious and quite concrete. Citizens share their needs, priorities and dreams for Milan in the coming years: bikesharing in the suburbs, longer service hours for the metro, a single card to access every museum in town. Some promise to think about it in depth; others volunteer to work with the new administration for free. As is often the case, the willingness to help of the connected citizenry took by surprise commentators not accustomed to the Internet social dynamics.

Granted, the 140 characters of Twitter are hardly suited to designing policy; it is unlikely that they will much further than a book of dreams. But a threshold has been stepped over: some of the mayor’s supporters are migrating from (partisan) cyberactivism to (nonpartisan) collaboration with a city institution. This is the same collaboration that I tried to account for in my book; I think it arises fairly naturally as a feature of civility in the 21st century. In this new space it will be natural for people that did not vote for Pisapia to participate, and they will be welcome. If the new Milan administration plays its cards right, it could give rise to a world class participation experience, in which citizens not only contribute to policy design, but to policy delivery as well. I recommend it goes for it: wiki government is very efficient, and not nearly as disruptive as it sounds. I am confident that the Milanese — not just those on Twitter, either — would play ball like there’s no tomorrow.

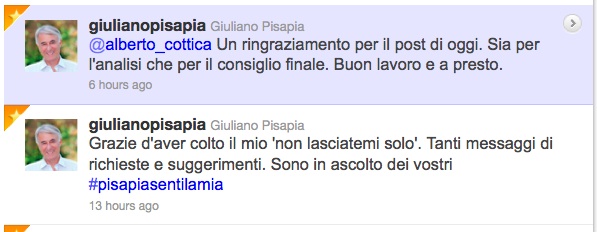

UPDATE: a few hours after this post went online Pisapia tweeted that he is reading all #pisapiasentilamia suggestions and grateful to everyone putting them out. That’s very good angling: he is not committing to act on the basis on those suggestions (indeed he could not do so), but simply to read them and take them into consideration. In a separate tweet he thanked me for the post. Meanwhile a #pisapiasentilamia showed up on Facebook.