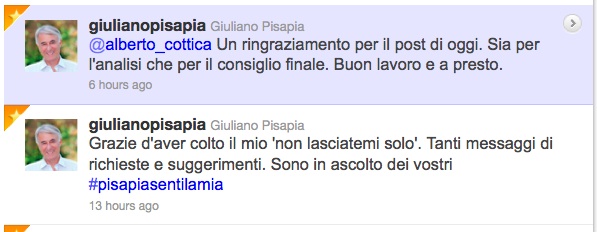

The time has come for open government in Italy. As so many phenomena here, it is not immediately apparent because it starts from the fringes and spreads unevenly, rather than being set in motion by a strategic decision of the State, as happened in the USA and in the UK. In this phase, it seems, the movers and shakers are city administrations: just look at ePart in Udine, Karaliscrazia in Cagliari, Wikicrazia in San Benedetto del Tronto. The newly elected administration in Milano is expected to make a move soon: meanwhile, the mayor Giuliano Pisapia and, even more so, the alderman Stefano Boeri (very active on Facebook) entertain a rich social media conversation with their fellow citizens.

Digging deeper, though, it becomes clear that the real protagonist in this phase of Italy’s transition to an open government is the civil society. The San Benedetto initiative was kickstarted by a group of citizens and a local paper; in Cagliari the initiatives are two (Karaliscrazia and Ideario per Cagliari), and both spawned from the civil society; as for Milano, the openings towards Internet-enabled collaborative governance are championed by an association called GreenGeek, that proved itself able to ferry the connected citizenry from campaigning to get Pisapia elected over to collaborating with his administration. Local administrations are being more reactive than proactive (the exception is Udine, where the ePart project was initiated by the mayor). The Italian way to open government, then, is characterized by a double anomaly: it is local rather than central, and the civil society is blazing its trail in a way that it does not in other countries.

More cities are to follow. These days, with each passing week more individuals, citizens’ groups and administrations are getting in touch with me to let me know they are thinking of launching yet more initiatives of collaboration between citizens and administrations: they want to discuss withme, or invite me to public events. I feel honored and proud that many of them are using my book Wikicrazia as a user’s manual for collaborative governance: a tool not just for learning about the wiki government, but for actually going out and making it happen.

Such a wealth of participation is a great asset, but it involves a risk: that of administrations feeling cornered, and perceiving as contrived a collaboration that should be completely natural. My first advice to people that ask me “how should we do this?” is always the same: you need to get the mayor or someone in the administration to sign up to your project, so be prepared to tailor it in a way such that they are comfortable with it even if this means giving up on some of your ideas. Sure, citizens have every right to make proposals in any way they want: but making proposals is not open government. Open government requires an explicit collaboration between citizens and administrations: the latter hold the democratic legitimacy to make and implement decisions that, by definition, are going to affect all citizens, including those that do not participate in the collaboration.

In the coming months I intend to blog about the many stories of local collaborative governance cooking up or already out there in Italy and elsewhere. I would like to X-ray them, not to criticize but to distill the best ideas and practices from all this civic energy. If you know any, I would be grateful if you dropped me a line: you can find me on this blog, the main social media and by email at alberto[at]cottica[dot]net.